Restaurant Row on King St West, site of a proposed 47 story condo that should preserve the restaurant facades but will dramatically change their context.

When I led a field trip for the Society of City and Regional Planning Historians in October through the west side of downtown, a sort condo feeding frenzy was underway – new towers dwarfing ones only fifteen years old, cranes everywhere, and rezoning signs on King Street both for the popular restaurant row on and for three 80+ story skyscrapers in the theatre block. I wrote about Toronto as a skyscraper city in Chapter 5 of my book, but things seemed to be moving into another dimension. I intended this post to be a brief update to capture some of these changes, but then I discovered that several sources I used in Chapter 5 have been recently updated and deep divisions of opinion about what is happening. The result is this rather long post about condo towers downtown, who lives in them, what the planning constraints are, and what problems they might have.

————

Pros and Cons

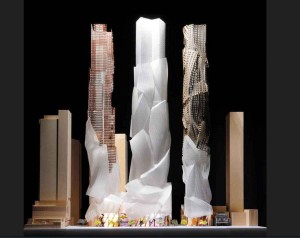

According to Emporis, an organization that monitors skyscraper construction around the world, in early 2014 Toronto currently has more skyscrapers over 100 meters (about 30 stories) under construction than any other city in the North America. There are proposals for ten towers over 70 stories (three of them designed by Frank Gehry at more than 80 stories) and for another eight over 60 stories. (Probably because these are designed by a celebrity architect, these have been enthusiastically endorsed by some Torontonians, but for Gehry’s critics the wavy, gauzy effect will reinforce the view that he is the world’s worst living architect.) These towers will add to about 200 skyscrapers already in the city, most of which are condominium apartments and are concentrated downtown.

Three proposed condominium towers over 80 stories designed by Frank Gehry on the theatre block owned by David Mirvish on King St West. The proposal is currently under review.

Chris Atchison thinks that intensification and skyscrapers on this scale are highly beneficial to the city. Writing in the Globe and Mail in September 2013 under the headline “Supersized Skyscrapers: Win-Win Developments?” he claimed that: “Ultra-tall mixed used towers that offer breathtaking views to attract residents and investors alike allow developers to maximize land use and boost profit margins.” His view is apparently widely shared because developers continue to build and propose ultra-tall condos, and people keep buying the units in them. Marcus Gee has a rather different perspective – he thinks Toronto’s plans to focus intensification, even at levels he calls ‘hyperdensity’, are working well because they allow the far more extensive relatively low-density areas of Toronto to remain essentially unchanged.

Others, however, have serious doubts about what Adam Vaughan, the councillor for the area where high-rise development is currently most concentrated (and cited by Marcus Gee), calls “vertical sprawl.” Konrad Yakabuski, for example, thinks Toronto has “an unhealthy height obsession” and that super-tall condos are “a lipstick on a pig approach and show an almost total disregard for their surroundings. Gehry’s proposed towers may have fancy cladding, but they are would be about twice the height of the recently completed LIghtbox condominiums and five times as tall as the former Metro Hall, both of which are on adjacent city blocks.

Brian Tuckey of the Building Industry and Land Development Association, cited here, raises the fact that almost all residential construction in Toronto is currently of high-rise condominiums, mostly with small units suitable only for singles or childless couples. He thinks the real housing demand is for what he calls “ground-related product,” in other words townhouses and houses and sees no end in sight for the rising cost of these because so few are being built. His argument is supported by the City’s background report on the 2011 Canadian Census which shows that in the previous five years Toronto’s population grew by 112,000, yet over 90 percent of the dwellings constructed to accommodate this increase were apartments.

And a CBC documentary in November 2013 called “The Condo Game” suggested that developers have little interest in the durability of their condo towers because they make their money as soon as the skyscrapers are turned over to condominium associations, which are ill-prepared to deal with deferred maintenance issues of skyscrapers that in 15 to 20 year may include complete recladding of the fully glazed towers currently in fashion and/or replacing aging elevators, both of which will cost millions and disrupt the lives of residents for weeks. This February article in the Toronto Star makes a similar point about the costs of maintenance.

There is no doubt that skyscraper condos constitute a substantial change to the urban form and streets of the central city, but I have found most of the articles about them strong on opinions and short on evidence about this conflation of skyscraper building, condominiumization, intensification and population growth in downtown. This post summarizes information to some straightforward questions: What is downtown? What are condominiums and what particular challenges do skyscraper condos face? What are the trends for building apartment towers in Toronto? What is known about who lives downtown and the growth of population there? What are the planning guidelines for tall buildings?

There is no doubt that skyscraper condos constitute a substantial change to the urban form and streets of the central city, but I have found most of the articles about them strong on opinions and short on evidence about this conflation of skyscraper building, condominiumization, intensification and population growth in downtown. This post summarizes information to some straightforward questions: What is downtown? What are condominiums and what particular challenges do skyscraper condos face? What are the trends for building apartment towers in Toronto? What is known about who lives downtown and the growth of population there? What are the planning guidelines for tall buildings?

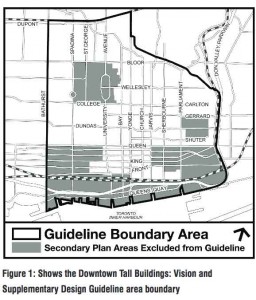

Downtown Toronto

Downtown is where skyscrapers, whether offices or condos, the financial district and the major institutions are concentrated. There are some online discussions about the precise boundaries that take Bloor Street as the northern boundary, but the definition in Toronto’s Official Plan, shown below on the left, makes better sense both because it includes the tall buildings on both sides of that and because it is used in most City reports. I note, however that the City’s “Guidelines for Tall Buildings Downtown” uses a subset of this that excludes the waterfront, the University of Toronto campus/Provincial legislature, and King-Parliament and King-Spadina – the areas where the condominiumization of downtown began and for which there are secondary plans. I also note that high-rise development is now spreading beyond the western boundary.

Condominiums

Condominiums are a form of collective living consisting of individually owned units in larger buildings. Some version of them is thought to have existed since at least the Romans, but they were not introduced to North America until 1960, specifically in Salt Lake City. In 1968 Ontario passed its first condominium act, and a revised version was passed in 1998 (currently under review). A condominium is a type of corporation, with a board of directors elected from among the unit owners that has responsibilities for managing the condo’s budget with attention to the maintenance of common elements, including roofs, outside walls and windows, corridors, elevators, plumbing stacks, electrical rooms, parking areas, recreational facilities, lobbies and landscaping. Even though boards usually hire management companies to assist them, for a condo of several hundred units in a glass-walled skyscraper of 50 or more stories, and annual budgets of several million dollars, this is obviously a substantial responsibility,

In 2013 more than a million people in Ontario were living in over 500,000 condominium units. In the City of Toronto about a quarter of all dwellings are condominiums. They can exist in many different forms, including townhouses and low-rise apartments, but data on construction for the City of Toronto for the last few years shows that more than 90 percent of dwellings completed have been apartments of five or more stories with the rest divided about equally between townhouses and detached houses.

Concord Place Condominiums between Spadina and Bathurst

It has been suggested that the boom in skyscraper condominium apartments in dense urban centres is because condos now provide the only affordable way for most people to buy somewhere to live, and are the only affordable way for developers to build (though for developers I suspect that it may be more a matter of maximizing profits). In the Toronto region (the CMA) the number of condo completions has risen from about 6,000 in 2000 to 18,000 a year now, which is considered to be about the limit given the number of construction workers and amount of equipment available. Real estate data specifically for the City of Toronto show that in 2013 13,797 condominium units were sold, the average price was $381,000, the average size was 796 square feet, 40 percent were one bedroom or one bed with den, and 42 percent had two bedrooms. Only 8 percent had three bedrooms, and the average price of those was $800,000. This is significant because a three-bedroom dwelling is usually what is considered necessary for a family with two children, so apparently only wealthy families can afford condominium apartments in Toronto.

Skyscrapers and the Growth of High-Rise Living in Toronto

Definitions of skyscrapers vary considerably. One key source of international information, Emporis, uses 100 meters or more architectural height (not including antennae or spires – about 30 stories); by this measure the City of Toronto has 187 and ranks 7th globally. Skyscraperpage, another good source of international information, uses 12 stories or more (about 35m), the height of buildings to which the word ‘skyscraper’ was applied when it was coined in the late 19th century; by this measure Toronto has 1987 and ranks second in the world after New York City.

The Canadian Census and City of Toronto collect date for neither 100m nor 12 story buildings, but they do have information on apartment building of five or more stories. In 2011 the Census counted 1,048,000 dwellings in Toronto; 429,000 were in apartments of 5 or more stories (41%), 165,000 in apartments less than 5 stories (16%), 275,000 detached houses (26%), 116,000 semis or duplexes (11%), and 160,000 townhouses or row houses (15%). With these proportions it’s not difficult to see why there might be concerns about the fact that 90% of dwellings constructed in the last few years have been condominiums.

Skyscraperpage includes a timeline of tall buildings built over the last 50 years (actually back to before 1900) and using this it is possible to trace the evolution of the skyscrapers in Toronto (I have a drawing of the changes to the downtown skyline in Chapter 5 of my book).

- In 1960 there were about 25 buildings of 12 stories or more. The only buildings over 100m were Commerce Court, the Royal York, the old Bank of Nova Scotia building at King and Bay, and the tip of the tower of Old City Hall at 103.6m. None were residential.

- By the end of 1970 41 towers of twelve or more stories had been added, including the first two towers of the Toronto Dominion Centre and New City Hall. Office towers were downtown but at least 20 were apartments (this may be an undercount because Skyscraperpage doesn’t seem to include Metro social housing) distributed across the city – in Forest Hill, the Annex, Jane Street, York Mills, Scarborough, etc. The two 44 story (130m) Leaside Towers overlooking the Don Valley were built in 1970. In the 1970s another 100 or so apartment towers were built across the city, mostly of 20-30 stories. Towers at Charles St West, Crescent Town, Harbour Square and Harbourside Apartments and Palace Pier were over 100m.

- From 1980 to 2000 the high-rise apartment building surge dropped away and only about 30 high-rise apartment towers were completed, with just two over 40 stories.

- A building surge began in 2000 with about 50 towers over 12 stories completed in the first 5 years of the new millennium, 20 of them over 100m. These were initially dispersed across the City, along the waterfront, in North York and elsewhere. The concentration in the downtown core began about 2005, and between 2005 and 2010 about 50 tower apartments were built, most of them downtown, 33 over 100m including 15 at more than 40 stories, and another at 6 at more than 50 stories,.

- Since 2011, another 93 apartment towers over 100m have been completed or are under construction, the tallest at 78 stories (Aura at Yonge and Gerrard opened late 2013), a dozen over 50, 25 more over 40, again most of them downtown. There are currently proposals for 10 buildings over 70 stories, and another 8 over 60, all downtown.

In short, a skyscraper in 1914 in Toronto was a building with 12 stories or more, and there were fewer than 10 of those; none were residential. The tower of Old City Hall was the tallest structure in the skyline. Now there are almost 2000 buildings of 12 or more stories in Toronto, 187 of them over 100m.

- – in 2000 there were about ten residential towers of 100m or more in Toronto

- – in 2005 there were about 30,

- – in 2010 there were about 60

- – in 2014, including towers under construction, there are more than 150.

This may be confirming what seems obvious, but over the last ten years the rate of construction of skyscraper apartment towers has accelerated, the towers have become taller and, in marked contrast to the distributive practices that applied before 2005, they have been increasingly concentrated not just in downtown Toronto but in the core of downtown around the financial district and along the waterfront.

Who Lives Downtown?

A 2007 report by the City of Toronto titled Living Downtown indicated that the population of the central area had increased by 70,000 between 1976, when the Central Area Plan was made, and 2006. This growth number can be updated using information from the 2011 census in the City’s Ward Profiles (a ward is an area represented by a city councillor) for Wards 20, 27 and 28, which together correspond closely with downtown as it is defined in the Official Plan. Downtown population growth 2006-11 was about 46,000 and constituted 40% of the population growth for all the City of Toronto. To put it differently, downtown population in those five years grew from 176,000 to 222,000, a 25% increase – compared with a 4.5% increase for the whole City. In other words, population growth was highly concentrated downtown.

Living Downtown and in the Centres is a 2012 update to the Living Downtown study that also considers the four urban growth centres that are identified in the province’s Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe (specifically North York, Yonge/Eglinton, Scarborough and Etobicoke). It is based on a survey that had 5,199 responses, 1,300 of them from residents of downtown. From that and the City’s Ward Profiles the following information is available:

- Half the downtown population lives in single person households and almost half is aged between 20 and 40, about twice the City average

- 60% of downtown residents are university graduates and almost 20% of the households surveyed have incomes greater than $150,000

- 60% of dwelling units are bachelor or 1 bedroom

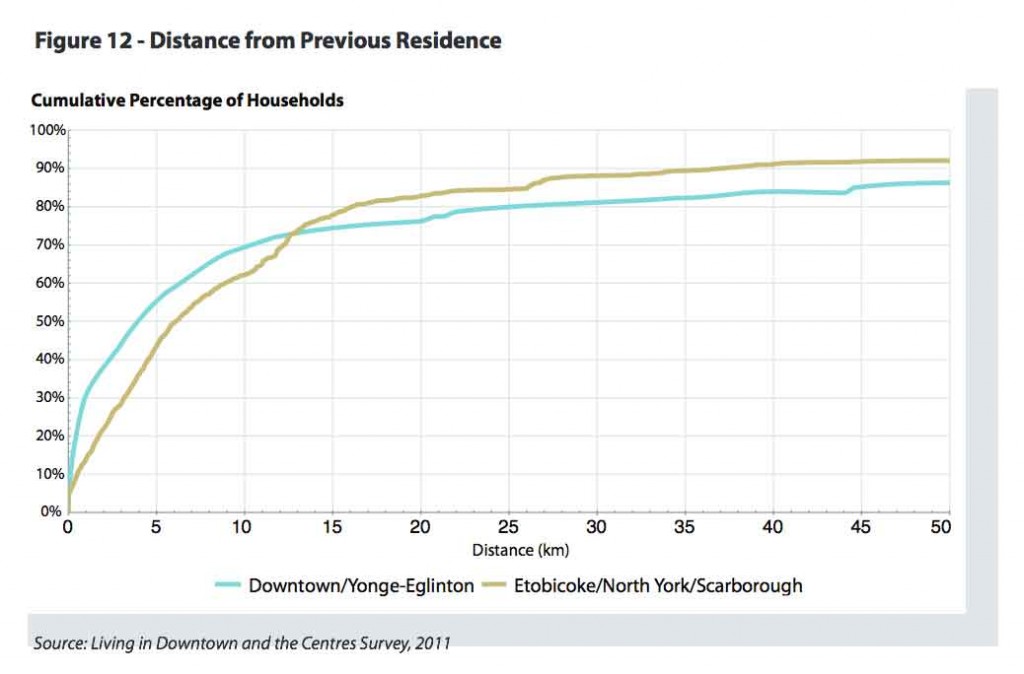

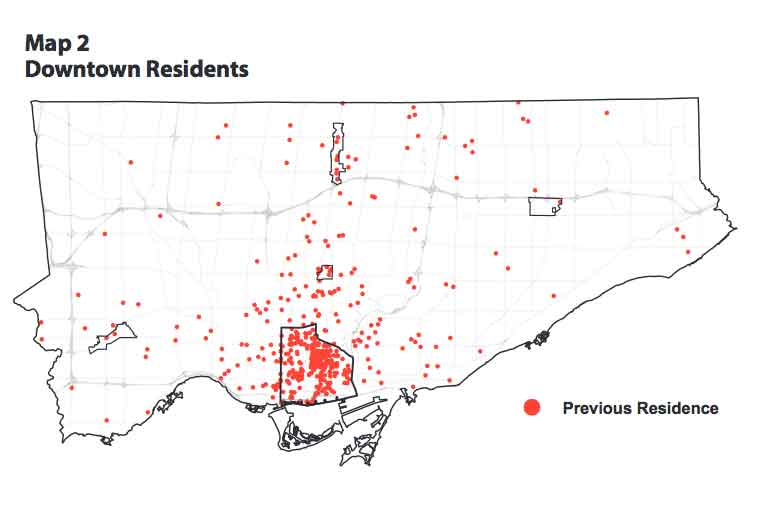

The 2012 report asked how far residents had moved from their previous dwelling and the conclusions are revealing:

- 11% had moved within the same building, 33% had moved from another location in downtown, 30% from elsewhere in the City, 13% came from the GTHA and 12% from elsewhere in Canada

- 55% of downtown residents had moved less than about 5 kilometers, and 70% had moved less than10 kilometers from their previous dwellings

The graph and map below from “Living Downtown and in the Centres” that clearly illustrate the relatively short distances downtown residents had moved. They suggest that the substantial population growth downtown does not involve a migration from the suburbs so much as a churning of population within and close to downtown.

The survey for ‘Living Downtown and in the Centres’ identified problems of living in the central city as:

- Car traffic/congestion (21%)

- Noise (14%)

- Affordability (13%)

- Homeless people (8%)

- Too few parks (7%)

- Pollution (6%)

- Transit problems (5%).

The survey also found that most of the downtown respondents feel cramped in their current apartments because 25% of them hope to move to larger dwellings of some sort, though only 14% expect to move out of downtown. Given the small size of most of the apartments downtown and the fact that so few houses and townhouses are being built anywhere in the City, this appears to be wishful thinking.

Planning for Tall Buildings Downtown

Toronto has both city-wide guidelines for tall buildings and specific guidelines for tall-buildings downtown that were updated in 2013.

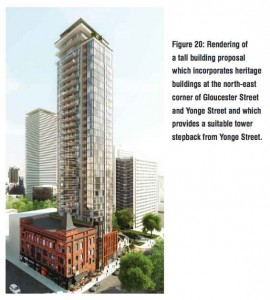

Illustration from Downtown Tall Buildings, showing heritage protection in relation to skyscraper construction

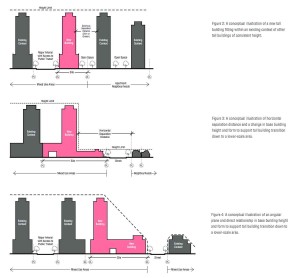

The city-wide guidelines discourage slabs (because they cast big shadows), and free standing towers surrounded by open space (the standard practice from about 1955 to the 1980s). They aim to minimize adverse wind conditions by using design features such as step backs and canopies to reduce downdrafts. They require transitions to lower-scale areas, and they require towers to be located and designed to respect the scale and form of on-site and adjacent heritage properties. The minimum tower separation is 25 meters, and this is increased for taller towers. An important aim is to relate tall buildings to streets: “A well-designed and vibrant streetscape is vital to the character and quality of the tall building site and the surrounding public realm, as well as the livability of the city” (page 58).

This view of lower Spadina Avenue shows the difficulty of achieving a semblance of a conventional streetscape in an area of skyscraper condos.

The guidelines for “Downtown Tall Buildings” stresses the fact that this is an urban growth centre in the provincial Growth Plan and high-rise development is needed to meet the density goals of that regional plan. The Toronto Official Plan gives no overall height and density limits for downtown – they exist only where they have been determined on the basis of area reviews. The core area around King and Bay west to Spadina has no limits.

The specific aim downtown is to fit new development with existing and planned contexts in order to achieve compatibility with other buildings, public spaces, streets and “lower scale neighbourhoods.” There are several heritage districts and many individual designated buildings downtown and the guidelines stress the importance of protecting these and low-rise neighbourhoods by stepping the towers well back behind them.

Diagram from Downtown Tall Buildings showing various guidelines for spacing skyscrapers and relating them to existing development and streets.

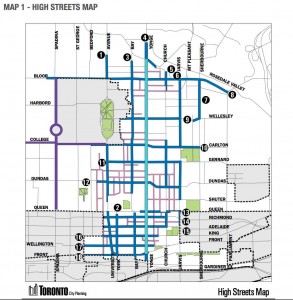

To achieve these aims the guidelines for downtown tall buildings distinguish:

- High Streets (some sort of pun, I suppose) – major downtown streets suitable for tall buildings

- Secondary High Streets that run between or adjacent to High Streets, and have mostly residential apartment buildings, where tall buildings are also appropriate

Map of High Streets from Downtown Tall Buildings. High Streets in blue, Secondary High Streets in pink. Incidentally, this illustrates the awkwardness of excluding areas with Secondary Plans that are shown in grey.

Three street forms for High Streets are identified –

- Tower base forms = slender point towers on “pedestrian-scaled base buildings” or podiums that define the street edge

- Canyon forms–street walls with tall buildings that cover the full width of the lot

- Landscape set back form – mostly to preserve heritage buildings – where the tower is set further back from the street.

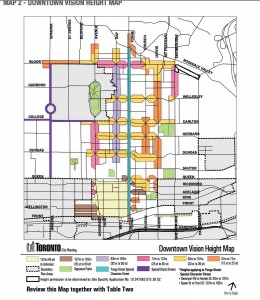

Downtown Vision Height Map from Tall Buildings Downtown shows suggested height limits for High Streets. The pale yellow area (the financial district) has no height limits. Yonge Street is a special study area, which in practice seems to mean that very tall towers can be built along it as long as they keep a bit of the facade of old low rise commercial buildings.

A key aim of planning is to direct urban change so that deleterious environmental and social effects are reduced, and the tall building guidelines are a commendable effort to control a rapidly changing development phenomenon by maintaining a semblance of pedestrian friendly forms at street level. Yet even though they were updated in 2013, I have they impression they are playing catch-up. Most of the photos in the guidelines are of towers that already seem rather modest. The downtown Vision Height Map seems to give no indication of the 78 story Aura tower at Yonge just south of College that has just been completed, and proposals for 80 story towers by Frank Gehry and others at the foot of Yonge Street are both out of the area it covers. The Gehry proposal was turned back for review in December because, according to Chief Planner Jennifer Keesmat, it lacked a meaningful heritage strategy, it size and orientation were inappropriate, it lacked private amenity space, and made no contribution to community facilities, all issues clearly addressed in the tall building guidelines. This suggests that downtown is becoming a sort of playground for condominium developers trying to get away with whatever they can.

COMMENTARY

It is clear that the downtown skyscraper condo boom is a recent phenomenon that began only about ten years ago and that it is a demographic, geographic and architectural deviation from all previous urban development practices in Toronto.

Glassy skyscrapers (one is a hotel) towering over what street signs call the Village of Yorkville demonstrate the remarkable change in urban form that is underway.

Recent high-rise condominium construction has brought population to the parts of downtown close to the financial district, it has been a huge factor in the City’s recent population increases, and has enabled the City to meet the targets of the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe which identifies downtown as the most dense urban growth centre in the region. But it would be unwise to ignore concerns about the types of buildings, future responsibilities of condominium associations, and the limited number of families that are being accommodated downtown. For instance:

- Many recent condominiums towers are sheathed in windows – in part for design but probably also because glass is a relatively inexpensive building material. The Tall Building Guidelines encourage sustainable design and green building performance, but fully glazed walls are thermally inefficient, and inclined to leak.

- The tower renewal programme currently underway in the Greater Golden Horseshoe, which aims to retrofit and repair towers, almost all under 30 stories, built in the 60s and 70s, gives a good indication of the long-term problems of maintaining high-rise apartments. The CBC’s Condo Game documentary noted that for glassy condo towers there is a significant possibility that seals and caulking will begin to fail after 15-20 years, the cladding will have to be replaced, and owners will have to move out while this is being done because their units will be without an exterior wall. The costs of recladding will be many millions of dollars even for relatively modest towers, and if these costs have not been covered by setting aside large reserve funds high special assessments will be needed to pay for them. It is not impossible that this could cause problems on a scale comparable to that of the leaking condos in British Columbia in the 1990s .

- The Living Downtown surveys indicate that the owners of these new condominiums are mostly relatively young. While they indicate a desire to stay downtown they also want more space in their units, and if they have families they will certainly need that. However, very few new dwellings being built anywhere in the city that they could move to. The fact that 90% of new dwellings in Toronto are apartments, almost all in towers, represents a very substantial deviation from previous practice. It is possible to accommodate families in high-rise development – it has been achieved in Yaletown in Vancouver – but this requires some larger, affordable units, and neighbourhood schools and playgrounds which so far have been part of the recent skyscraper boom downtown.

- Yaletown has been successful in providing facilities for families in large part because of major revisions to the BC condominium legislation following the leaky condo crisis. It is to be hoped that the current review of Ontario’s condominium legislation will attend to the the accommodation of families and to the possible problems of glass-wall skyscraper construction.

- The condo boom downtown began in the late 1990s with the dezoning of King-Parliament and King-Spadina industrial/commercial areas (discussed in Chapter 5 in my book on Toronto). The intent was to relax land use constraints yet maintain existing built forms, so the first condos were modest buildings of 10 to 20 stories, such as the one shown below. My impression is that the Guidelines for Tall Buildings make excellent sense for that sort of scale, but at 70 and 80 stories the canyons and peaks are at an entirely different order of magnitude. Heritage preservation of three story brick buildings in a cityscape of 80 story glass towers really does seem like a lipstick on a pig approach.

The corner of KIng and Spadina. The twelve story tower just behind the brick building is a condominium completed about 2001, consistent with the initial aims following dezoning of fitting new building with older urban forms. In the background are several recent skyscraper condominiums.

Finally, I am far from convinced that these super-tall skyscraper condominiums are the only or best way to achieve the high densities demanded in the provincial Growth Plan or as way to reduce pressure on transit because people can walk to work in offices in the central city. Here are my reasons:

- The Growth Plan density targets are for jobs+people, and the CBD is currently going through a boom in office construction. In late 2013 a quarter of all the office space under construction in Canada was in downtown Toronto and the new jobs created will offset the number of people needed to meet the target.

- Ward Profiles for the City include summary information on density and on number of apartments in buildings of five stories or more, apartments in buildings of less than five stories, and on number of houses. Ward 20, which includes the west side of downtown where the population rose from 49,000 in 2001 to 76,600 in 2011, is the ground-zero of condominium skyscraper constructions and proposals. It has 51% of the population in one-person households, 64% living in apartments of 5 stories or more. The population density is 10,270 per square kilometer (the highest in the city). Ward 14 is Parkdale, an area mostly of late-19th century streets, has only 40% of its population in apartments of 5 or more stories (and almost none of the really tall ones), 36% in apartments of less than 5 stories, and 25% in houses or row houses. It has a density of 9,490 per square kilometer (the second highest in the city).

- St Lawrence Neighbourhood provides an excellent local model of intensification that has increased population close to the downtown core in ways that are both street and family friendly.

In the short-term, then, I think ultra-tall glassy condo towers promise glitz, glamour and convenience for their mostly thirty-something occupants who have moved from not very far away and can now walk to work and to clubs and restaurants. However, from a long-term perspective there are numerous reasons to doubt whether they will be beneficial contributions to sustainable urban forms that can be reasonably easily adapted to changing social, economic and environment conditions in ways that will maintain the organized complexity of the city of Toronto. But skyscraper condos are in fashion, and it seems probable they will continue to be the preferred approach to intensification downtown until the boom ends or there are no more sites to build on.