This page is part of the companion website to my book Toronto: Transformations in a City and its Region, published by UPenn Press.

This page is part of the companion website to my book Toronto: Transformations in a City and its Region, published by UPenn Press.

The End of the Inward-Looking City

The intensity of the change in Toronto between about 1970 and the present day can be conveyed in comparisons of photos taken then and now. The ones below are of Kensington Market, now an idiosyncratic, colorful, trendy and culturally diverse area of a few streets of small stores and cafes on the western edge of downtown; in the 70s it was still mostly a Jewish market with bagel stores and live chickens and dead rabbits outside butcher shops that reflected its early 20th century origin as a handcart market created because WASP stores wouldn’t sell to Jews and new immigrants.

- Baldwin Avenue in Kensington Market about 1971

- Roughly the same view on Baldwin in 2013

- Kensington Market, c 1971

- Fruit and vegetable display, Kensington Market 2013

And just to reinforce the point about the change, here’s Bloor Street (on the left) just west of Brunswick Ave about 1969, and (on the right) the same bit of street in 1992. In 1969 it was a utilitarian commercial street lined with small stores, poles and wires, and no trees (trees had been considered an unnecessary frill on main streets in Ontario towns since the 19th century, perhaps because they got in the way of the wires). This was a popular bit of the city, near the University of Toronto and with taverns and Hungarian restaurants, yet there were not many pedestrians and absolutely no outdoor cafes (which were regarded as sinful because customers might be seen drinking a glass of wine by somebody on the public street!). The faded colours in the photo reflect well what I remember of the dusty, grimy character of Toronto in the late 60s. In 1992 the wires were gone, there were planters with street trees, and sidewalk sales and (though not shown here) patio cafes had opened.

And just to reinforce the point about the change, here’s Bloor Street (on the left) just west of Brunswick Ave about 1969, and (on the right) the same bit of street in 1992. In 1969 it was a utilitarian commercial street lined with small stores, poles and wires, and no trees (trees had been considered an unnecessary frill on main streets in Ontario towns since the 19th century, perhaps because they got in the way of the wires). This was a popular bit of the city, near the University of Toronto and with taverns and Hungarian restaurants, yet there were not many pedestrians and absolutely no outdoor cafes (which were regarded as sinful because customers might be seen drinking a glass of wine by somebody on the public street!). The faded colours in the photo reflect well what I remember of the dusty, grimy character of Toronto in the late 60s. In 1992 the wires were gone, there were planters with street trees, and sidewalk sales and (though not shown here) patio cafes had opened.

But evidence of the old, puritanical “Nobody Swings on a Sunday” attitudes (referred to in my book) does linger on. These No Hockey signs are not uncommon, though I suppose few kids pay attention to them nowadays.

But evidence of the old, puritanical “Nobody Swings on a Sunday” attitudes (referred to in my book) does linger on. These No Hockey signs are not uncommon, though I suppose few kids pay attention to them nowadays.

About three-quarters of my book on transformations to Toronto (and this website) deals with changes since 1970, both in its downtown streetscapes, but also its apparently inexorable expansion into a polycentric urban region with an increasingly diverse population. To understand these I think you have to know something of previous transformations that occurred after its founding in 1793, and about a quarter of my book (and therefore this website) describe these and how they impact current urban landscapes. Before I get to this substance, however, and to parallel the book, I want to provide some illustrations to reinforce my discussion in the book about biases and problems with urban language.

Downtown Bias

This Google Earth image gives an indication of the scale of the metropolitan area of Toronto, reaching to Hamilton in the west and just as far east and north. The green borders around Toronto are those of the current (post 1998) city, which was previously Metro Toronto. The red dot for Toronto is about the size of the downtown core – the area that seems to get most media attention and attract most tourists.

Urban description and analysis tends to be uneven in its coverage. The great majority of media reporting, TV coverage, website content and academic research about cities focuses on older areas close to downtowns. Relatively little attention is paid to automobile-oriented suburbs developed since about 1950, except perhaps to criticize them, even though in many cities these comprise most of the built-up area. In the case of Toronto most attention goes to the parts of the city built before 1940 when streetcars were the main way to move around, and where there are mass transit, pedestrian-oriented streets, entertainment districts, and a core of skyscraper condominiums and financial institutions. Yet in the current metropolitan area of the Toronto, the old, pre-1940 part (the old City of Toronto that was amalgamated with the inner suburbs in 1998) only has about 10% of the population and 2.5% of the area. In short, there is a marked imbalance the widely discussed and loudly advocated centrist perspectives of the old city, and the mostly unstated perspectives of the edge and outer suburbs. I think of this imbalance as a downtown bias.

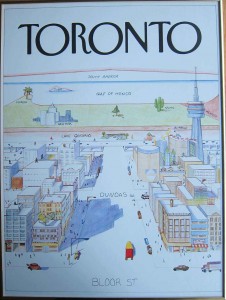

Here’s an example. I got this poster at a garage sale, and I don’t know the artist, but it is obviously based on Saul Steinberg’s famous illustration of New York City. It captures nicely the centrist perspective in which little outside the downtown core matters much because Toronto apparently ends just north of Bloor Street, about a mile from Lake Ontario. This may look like an over-exaggeration but I have heard a number of people express contempt for anything much north of Bloor. The June 2013 edition of the glossy magazine Toronto Life is slightly more generous. It lists 350 places to shop, eat and hang out, some of them north of Bloor but 340 of them are in the old city – the part built before 1940 with about 10% of the population. (The other 10 were all in Oakville, an affluent old small town on the lakeshore, halfway to Hamilton).

Here’s an example. I got this poster at a garage sale, and I don’t know the artist, but it is obviously based on Saul Steinberg’s famous illustration of New York City. It captures nicely the centrist perspective in which little outside the downtown core matters much because Toronto apparently ends just north of Bloor Street, about a mile from Lake Ontario. This may look like an over-exaggeration but I have heard a number of people express contempt for anything much north of Bloor. The June 2013 edition of the glossy magazine Toronto Life is slightly more generous. It lists 350 places to shop, eat and hang out, some of them north of Bloor but 340 of them are in the old city – the part built before 1940 with about 10% of the population. (The other 10 were all in Oakville, an affluent old small town on the lakeshore, halfway to Hamilton).

Urban Language

Vaughan is a rapidly growing outer suburb on the northwest border of the City of Toronto. By 2011 its population had increased to 288,000.

A difficulty that compounds the downtown bias is that much of the language used to describe urban areas is imprecise or ambiguous. To start with, there is no neat definition of a “city.” Is the city really the bit around downtown that Jane Jacobs praised in Death and Life of Great American Cities, with its compact forms and vibrant streets? This seems to be a common assumption (as in the Toronto Life example I just gave). But many suburban (i.e. built since 1950) municipalities, such as Vaughan, proudly call themselves cities.

Other urban words pose similar problems, “downtown” for example. According to destination signs on buses, local planning reports and so on, there are at least 20 downtowns in the Toronto region. Sprawl is a particularly problematic term (which I criticize in Chapter 6) often used as an implicit way to distinguish city from suburbs. As far I can tell it people use it to mean a type of urban development they don’t like. Region: Jane Jacobs in Death and Life, 438, wryly remarks that “A Region is an area safely larger than the last one to whose problems we found no solution.” And so on – density, heritage, development, environment, community, neighbourhood….

The gist is these words are often used as though their meaning is self-evident. In fact they are slippery, flexible and ideologically loaded. And here’s the rub. There are no substitutes. The fact is that we know what a city is when we are in one, and in discussing cities (by which I usually mean the built-up metropolitan area), these familiar words have to be used. Nevertheless, it’s obviously wise to pay attention to their imprecision.

Jacobs and McLuhan

In my book I use the ideas of two notable Torontonians – Jane Jacobs and Marshall McLuhan – to provide locally informed insights into the transformations of the urban region. This is rather theoretical and since this website is mostly a visual essay I don’t refer much to them here. Nevertheless I think it is helpful to illustrate their considerable public status in Toronto. Here, for example is a photo of the portrait of Jacobs in the grafitto that I illustrate at the end of my book. Coincidentally, this happens to be on a street only a block from where McLuhan lived. Jacobs has been publicly recognized through Jane’s Walks, an annual series of guided urban walks that began in Toronto and have been copied internationally, and an annual conference called “Ideas that Matter”, dedicated to her thoughts. Richard White, an urban historian, has assessed Jacobs’ local impact on urban development in “Jane Jacobs and Toronto: 1968-1978” Journal of Planning History, 2011, 10:114.

In my book I use the ideas of two notable Torontonians – Jane Jacobs and Marshall McLuhan – to provide locally informed insights into the transformations of the urban region. This is rather theoretical and since this website is mostly a visual essay I don’t refer much to them here. Nevertheless I think it is helpful to illustrate their considerable public status in Toronto. Here, for example is a photo of the portrait of Jacobs in the grafitto that I illustrate at the end of my book. Coincidentally, this happens to be on a street only a block from where McLuhan lived. Jacobs has been publicly recognized through Jane’s Walks, an annual series of guided urban walks that began in Toronto and have been copied internationally, and an annual conference called “Ideas that Matter”, dedicated to her thoughts. Richard White, an urban historian, has assessed Jacobs’ local impact on urban development in “Jane Jacobs and Toronto: 1968-1978” Journal of Planning History, 2011, 10:114.

The photo on the left shows how McLuhan has been acknowledged in a supplementary name for the street adjacent to the college in the University of Toronto where he taught. The CN Tower in the background offered itself as a photographic opportunity that I could not resist, though McLuhan, to my knowledge, never commented on its significance as a monument to electronic communication, perhaps because it represents almost the opposite of what he thought was the decentralizing impact of electronic media and their power to infiltrate every aspect of urban existence. “Every city is now a suburb of every other city,” he wrote in 1988, but as the photo of Vaughan above shows, a suburb can now also be a city.

The photo on the left shows how McLuhan has been acknowledged in a supplementary name for the street adjacent to the college in the University of Toronto where he taught. The CN Tower in the background offered itself as a photographic opportunity that I could not resist, though McLuhan, to my knowledge, never commented on its significance as a monument to electronic communication, perhaps because it represents almost the opposite of what he thought was the decentralizing impact of electronic media and their power to infiltrate every aspect of urban existence. “Every city is now a suburb of every other city,” he wrote in 1988, but as the photo of Vaughan above shows, a suburb can now also be a city.