This page is part of the companion website to my book Toronto: Transformations in a City and its Region, published by UPenn Press, 2014. Here is a link to the UPenn Press announcement.

This page is part of the companion website to my book Toronto: Transformations in a City and its Region, published by UPenn Press, 2014. Here is a link to the UPenn Press announcement.

Identity Problems: Names and Borders

Some cities, such as Portland, Vancouver and New York, have strong identities based in part on their setting and in part on skillful self-promotion. Toronto’s setting is unremarkable and it has been poor at self-promotion. It also hasn’t helped that both its name has changed several times.

Here’s some evidence of that. If you look closely at the yellow and white street signs they say “Town of York” – these were in the heritage district that was the original town site of York a few years ago; current street signs say generically “Old Town.” Metro no longer exists, of course, but its clever logo – a sort of Celtic knot pattern combining six circles, one for each of the municipalities, into a single cluster – was stamped into the concrete of bridges and other Metro installations, so it is still part of the urban landscape.

Here’s some evidence of that. If you look closely at the yellow and white street signs they say “Town of York” – these were in the heritage district that was the original town site of York a few years ago; current street signs say generically “Old Town.” Metro no longer exists, of course, but its clever logo – a sort of Celtic knot pattern combining six circles, one for each of the municipalities, into a single cluster – was stamped into the concrete of bridges and other Metro installations, so it is still part of the urban landscape.

This Welcome to Toronto sign (at the north-east corner in the Rouge Valley, which is the one remaining rural entry point to the City) shows the current, and I think less imaginative logo of the post 1998 amalgamated City that corresponds to what was previously Metro – an outline of New City Hall.

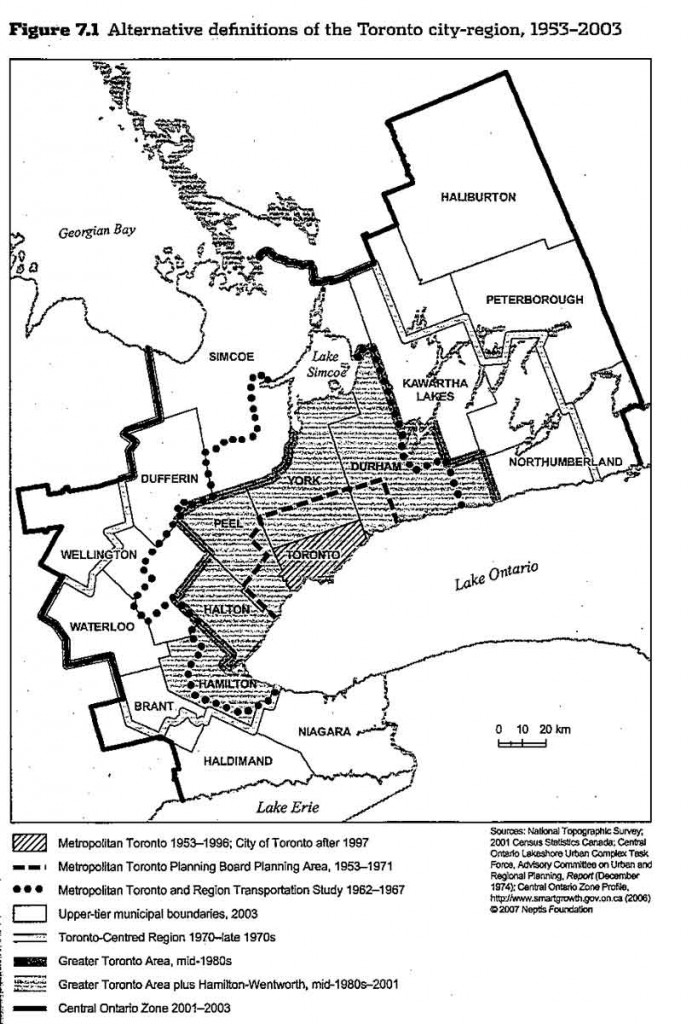

Confusion of names is little better at a regional scale. This map from Frances Frisken’s 2007 book The Public Metropolis, about policies governing the regional expansion of Toronto in the 20th century, shows the borders of eight different ideas about what constitutes the Toronto region, and it includes neither the Census Metropolitan Area nor the Greater Golden Horseshoe. With these sorts of inconsistencies and all the chopping and changing it has been difficult for a coherent urban identity to develop.

Frugal Utilitarianism

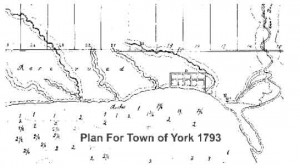

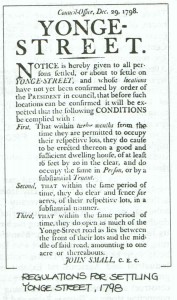

One theme that has been repeated throughout Toronto’s history has been frugality, often tinged with Presbyterian attitudes – straightforward and inexpensive solutions to problems, nothing too extravagant, creative or imaginative. I think this began the moment the plan for the Town of York was laid out with a simple grid of 10 squares, and the Queen Street was made a base line for the regional surver survey with long narrow lots perpendicular to it. This simple practicality was reinforced by the basic rules for settlers opening farms next to Yonge Street. York/Toronto was a capital city for Upper Canada but from the beginning there were no grand gestures in the town plan that might reflect this status.

This attitude of practical restraint continued throughout the 19th and much of the 20th century. It is hinted at in the name of Temperance Street in the heart of downtown (in the old City of Toronto there were “dry” neighbourhoods with no restaurants licensed to sell alcohol until almost the end of the 20th century). and then again in the Art Deco mural on the old Toronto Stock Exchange, a few blocks from Temperance Street, that mostly depicts streamlined hard work.

The mural below, which I photographed somewhere in the Niagara District just west of downtown sometime in the early 1990s, captured some of this long-established sense of a city devoted above all to making money (dollar bills floating down from the cash register in the sky), and by then beholden to the skyscrapers in the financial district – with the CN tower as a seductive distraction that apparently nobody wants to get too close to.

Toronto’s Identity Problems in Movies and Novels.

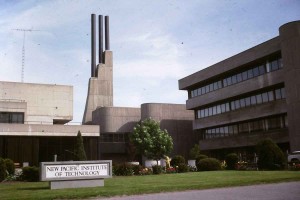

Frugal utilitarianism does not offer much for creative people to cling to. Hence, perhaps, Dan Ayckroyd’s comment (which I quote in Chapter 10) that Toronto is great for making movies because it can be made to look like almost anywhere. Here’s an example of that. This is the University of Toronto Scarborough (where I used to work), transported to the west coast for a movie that was being filmed there.

Frugal utilitarianism does not offer much for creative people to cling to. Hence, perhaps, Dan Ayckroyd’s comment (which I quote in Chapter 10) that Toronto is great for making movies because it can be made to look like almost anywhere. Here’s an example of that. This is the University of Toronto Scarborough (where I used to work), transported to the west coast for a movie that was being filmed there.

And perhaps it is the lack of any clear regional identity that gives rise to this sort of schizophrenia manifest in a remarkable sign on Highway 401 in Clarington, at the eastern end of the region, offering a choice between a fun farm and nuclear information. Or maybe this is just an idiosyncratic oddity.

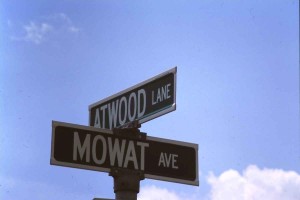

This street sign is in a subdivision in Oakville, where the streets have been named for local writers. Farley Mowat wrote robust accounts of the Canadian North; there are also street named for Hugh MacClennan, Morley Callaghan, Susannah Moodie and Stephen Leacock. I comment in Chapter 10 that novelists and writers, such as these ones recalled in street names in Oakville, rarely have had much positive to say about Toronto. This idea is excellently developed by Amy Harris in her recent book Imagining Toronto (Mansfield Press, 2010) that I had not seen when I completed my own book. She seems to have read just about every piece of creative writing that is set in Toronto, whether by internationally famous authors such as Margaret Atwood, Anne Michaels and Michael Ondaatje, or by authors with a mostly local reputation. Her book is filled with astute observations, and a central theme is that few Toronto authors express much positive enthusiasm for the city. The most common attitude is contempt, whether for the old City or, for the few books that consider the suburbs, for its new suburbs.

Spiral of Decline?

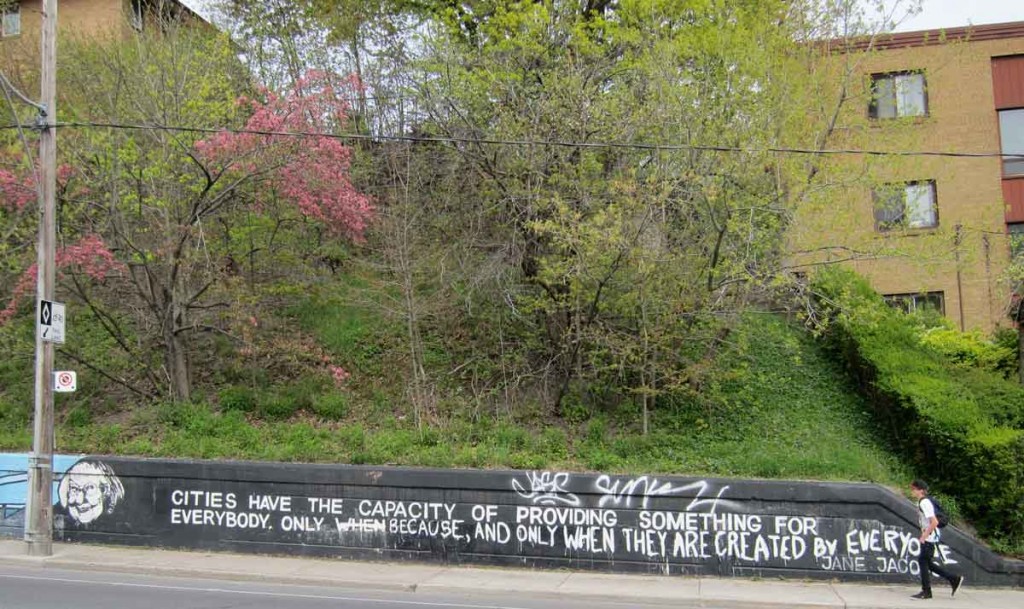

Jane Jacobs, who has been celebrated in portraits painted by Toronto street artists, such as this on Christie Street near Davenport, at one time celebrated Toronto’s diversity and organized complexity – the sort of thing represented in this small section of Queen Street West in Parkdale – an old main street block with a Vietnamese Restaurant and Cake(!), Mosque and appliance store. But I note in Chapter 10 that after the amalgamation in 1998 she came to see Toronto as a city in decline, not least because it was being dragged down by the suburbs with which with it was now combined. Some street artists seem to have shared this sense of despair. These photos I took about 2000; the “Heaven and Hell” one of Metro era apartments was at Markham and Ellesmere in Scarborough; “If voting changed anything they’d make it illegal” was in Kensington Market.

Jane Jacobs, who has been celebrated in portraits painted by Toronto street artists, such as this on Christie Street near Davenport, at one time celebrated Toronto’s diversity and organized complexity – the sort of thing represented in this small section of Queen Street West in Parkdale – an old main street block with a Vietnamese Restaurant and Cake(!), Mosque and appliance store. But I note in Chapter 10 that after the amalgamation in 1998 she came to see Toronto as a city in decline, not least because it was being dragged down by the suburbs with which with it was now combined. Some street artists seem to have shared this sense of despair. These photos I took about 2000; the “Heaven and Hell” one of Metro era apartments was at Markham and Ellesmere in Scarborough; “If voting changed anything they’d make it illegal” was in Kensington Market.

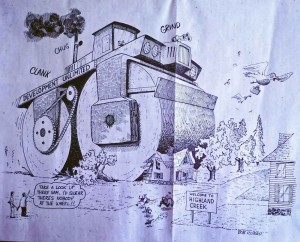

Utopia really does exist in the Toronto region – specifically a few kilometres west of the City of Barrie, but it is utterly rural and unrelated to any idea Jacobs might have had about ideal cities. It is still beyond the steamroller of urban development. This 1989 cartoon in The Villager, the community newspaper for Highland Creek, an old settlement in the suburb of Scarborough where I was living at that time, and which was itself being overwhelmed by newer suburban expansion, conveys a sense of Jacobs’ spiral of decline.

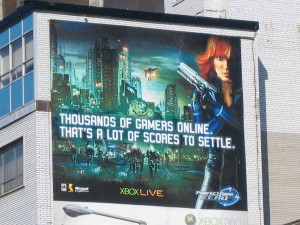

To my knowledge there are no street portraits of Marshall McLuhan but he does have a street and also a Catholic school named for him. I suggest in Chapter 10 that he would probably not have been much happier than Jane Jacobs with the way things have turned out in Toronto. Electronic media, which he claimed were having a fundamental impact on things, have become both commonplace and pervasive, changing cities in ways that we cannot yet begin to understand or anticipate. The backyard concrete model of the CN Tower I photographed in Brampton (Torbram Road?) about 1999, the XBox billboard with the Blade Runner background was on Bloor Street, not far from where Jane Jacobs lived, about 2005.

To my knowledge there are no street portraits of Marshall McLuhan but he does have a street and also a Catholic school named for him. I suggest in Chapter 10 that he would probably not have been much happier than Jane Jacobs with the way things have turned out in Toronto. Electronic media, which he claimed were having a fundamental impact on things, have become both commonplace and pervasive, changing cities in ways that we cannot yet begin to understand or anticipate. The backyard concrete model of the CN Tower I photographed in Brampton (Torbram Road?) about 1999, the XBox billboard with the Blade Runner background was on Bloor Street, not far from where Jane Jacobs lived, about 2005.

Rustbelt/Sunbelt City

In the context of all this confusion and despair, what can be said about Toronto’s identity. Well, first of all Toronto and the surrounding urban areas, which 50 years ago were based firmly on a manufacturing economy, have managed to avoid the fate of other rustbelt cities. The Toronto region has had levels of sustained growth, at least in population, that are consistent with those of sunbelt cities. This fact alone belies most of the criticisms, self-deprecation, contempt and confusions about its identity.

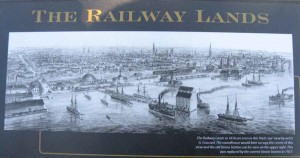

The illustration on the left is a photo of a heritage sign that shows the extensive industrial areas west of old Union Station (the building with three towers in the upper right) in 1876. Much of this area remained industrial for a century, but has now been redeveloped as a mixture of entertainment space (the Rogers Centre, a new aquarium, and the former roundhouse which is now craft brewery surrounded by a public park) and the condominium towers of Concord Place, shown in the photo on the right.

Manufacturing has mostly moved out of the old City, or has been integrated with new urban landscapes. The photo on the left below shows Sugar Beach, a new public park on the lakefront, with beach umbrellas, sand and water features; in the background is a molasses tanker at the Redpath Sugar Refinery. The photo on the right captures some the characteristics of post-industrial, creative Toronto – the floodlit CN Tower and Will Allsop’s shoebox building on stilts that is part of the Ontario College of Art and Design. More generally, Toronto and its region continue to prosper economically, even as much of the rest of the province languishes, especially because of its financial and creative industries

Management and Restraint

Toronto may have avoided the decline of other rustbelt cities, but the fact is that both Sugar Beach and dramatic architecture of the Ontario College of Art and Design are exceptional instances of flamboyance in an otherwise restrained urban setting. I suggest in my book that underlying Toronto’s identity, both in the City and the region, are principles of management and restraint, attitudes that have persisted since its founding in 1793. This is apparent in, for instance, the way in which the projects of celebrity architects are mostly additions to older projects – in other words, nothing too ambitious, just a little bit modern.

On the left is Frank Gehry’s remodelling of the facade of the Art Gallery of Ontario; the old part of the building is visible underneath the Creativity Lives Here banner. On the right is one of the towers of Mies van der Rohe’s Toronto Dominion Centre, awkwardly embracing the old Toronto Stock Exchange (the frieze of this is shown above in this web page). [Note: This sort of tempering of architectural expression is changing with condominium design – there are the Marilyn Monroe towers in Mississauga, a new tower by Daniel Libeskind (the L building) and a proposal for three 80 storey towers designed by Frank Gehry. Perhaps these presage some sort of shift to uninhibited urbanism, but I have serious reservations about the long term consequence of high-rise condominiums, their effects on street microclimates, and the costs of maintaining them.)

On the left is Frank Gehry’s remodelling of the facade of the Art Gallery of Ontario; the old part of the building is visible underneath the Creativity Lives Here banner. On the right is one of the towers of Mies van der Rohe’s Toronto Dominion Centre, awkwardly embracing the old Toronto Stock Exchange (the frieze of this is shown above in this web page). [Note: This sort of tempering of architectural expression is changing with condominium design – there are the Marilyn Monroe towers in Mississauga, a new tower by Daniel Libeskind (the L building) and a proposal for three 80 storey towers designed by Frank Gehry. Perhaps these presage some sort of shift to uninhibited urbanism, but I have serious reservations about the long term consequence of high-rise condominiums, their effects on street microclimates, and the costs of maintaining them.)

Here’s a detail that I think captures this sort of unnecessarily cautious, controlling attitude that has pervaded Toronto. In College subway station, which was the stop for Maple Leaf Gardens where the Toronto Maple Leafs used to play, there are murals of hockey players. These are clearly Leafs players, but the jerseys don’t have the complete insignia because the owner at the time – Harold Ballard – would not allow it to be depicted. The Montreal Canadiens on the opposite platform are, however, fully identified.

Here’s a detail that I think captures this sort of unnecessarily cautious, controlling attitude that has pervaded Toronto. In College subway station, which was the stop for Maple Leaf Gardens where the Toronto Maple Leafs used to play, there are murals of hockey players. These are clearly Leafs players, but the jerseys don’t have the complete insignia because the owner at the time – Harold Ballard – would not allow it to be depicted. The Montreal Canadiens on the opposite platform are, however, fully identified.

Here is a more mundane example – emptied recycling bins neatly lined up on the sidewalk of the street where I used to live in North Toronto. Toronto has a remarkable recycling programme – just about everything can be recycled without being sorted by homeowners – in part because it ran out of local landfill options about fifteen years ago and garbage had to be trucked to Michigan, and when that arrangement ended to landfill near London, Ontario. Recycling is the sort of thing Toronto seems to excel in.

Here is a more mundane example – emptied recycling bins neatly lined up on the sidewalk of the street where I used to live in North Toronto. Toronto has a remarkable recycling programme – just about everything can be recycled without being sorted by homeowners – in part because it ran out of local landfill options about fifteen years ago and garbage had to be trucked to Michigan, and when that arrangement ended to landfill near London, Ontario. Recycling is the sort of thing Toronto seems to excel in.

The pre-eminence of a functional management in dealing with urban landscapes is no less apparent in the inner and outer suburbs.

This statue of Gandhi at a Hindu Temple in Richmond Hill is apparently setting off on a pilgrimage under the power lines of the so-called Parkway Belt. And signs at the border of Peel Region convey very practical and down to earth attitutdes, caring and working for you.

This statue of Gandhi at a Hindu Temple in Richmond Hill is apparently setting off on a pilgrimage under the power lines of the so-called Parkway Belt. And signs at the border of Peel Region convey very practical and down to earth attitutdes, caring and working for you.

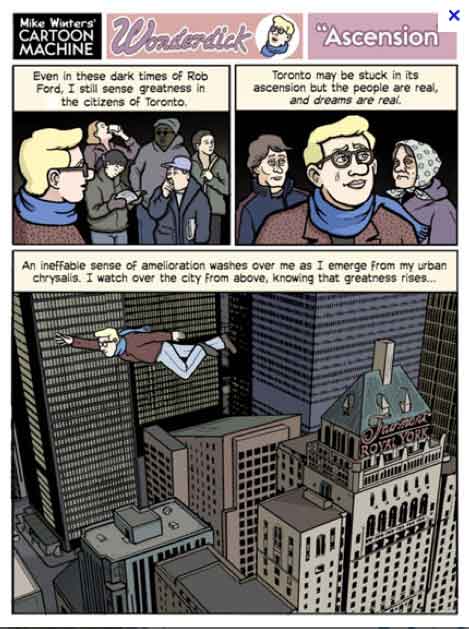

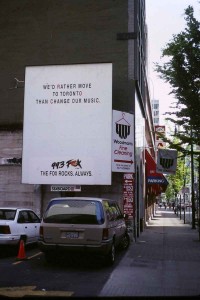

I am not sure whether it is because of these long-established attitudes of management and restraint, or the sheer scale of Toronto relative to other cities and regions in Canada, but Toronto has long been the object of ridicule by Canadians in other parts of the country. This radio station ad is an example from Vancouver which I photographed about twenty years ago. Toronto is popularly regarded in the rest of the country as a city that people should escape from rather than move to, a city generally to be avoided. A recent twist on this comes from cartoonist Mike Winters, now based in Edmonton but originally from Toronto, who has developed a strip about Wonderdick, a pretentious Toronto urbanite, a flaneur of the old City. Here is a selection from 2012 that is especially appropriate given the recent and embarrassing antics of Mayor Rob Ford that have made Toronto appear ridiculous on an international scale. Other cartoons about Wonderdick experiences in Toronto are available online.

I am not sure whether it is because of these long-established attitudes of management and restraint, or the sheer scale of Toronto relative to other cities and regions in Canada, but Toronto has long been the object of ridicule by Canadians in other parts of the country. This radio station ad is an example from Vancouver which I photographed about twenty years ago. Toronto is popularly regarded in the rest of the country as a city that people should escape from rather than move to, a city generally to be avoided. A recent twist on this comes from cartoonist Mike Winters, now based in Edmonton but originally from Toronto, who has developed a strip about Wonderdick, a pretentious Toronto urbanite, a flaneur of the old City. Here is a selection from 2012 that is especially appropriate given the recent and embarrassing antics of Mayor Rob Ford that have made Toronto appear ridiculous on an international scale. Other cartoons about Wonderdick experiences in Toronto are available online.

A City for Everybody

In the absence of any definitive identity for Toronto and its region, and given the paucity of positive endorsements by novelists and artists, yet also given the fact that the Toronto urban region has a fifth of Canada’s population, has avoided most of the problems of rustbelt cities or the sort of concentration of deprivation of Vancouver’s east side, and is consistently ranked near the top in global assessments of the best cities to live, it clearly offers something positive to both old residents and new immigrants. As far as I can gather, this stems from the persistence of deep and pragmatic attitudes that focus on keeping things functioning moderately well and have facilitated both the remarkable vitality of the old City and the sustained growth of the urban region. Given this, and also because half of the people in the region have come from other countries, it is not unreasonable to claim that Toronto does indeed provide something for almost everybody.