This page is part of the companion website to my book Toronto: Transformations in a City and its Region, published by UPenn Press.

This page is part of the companion website to my book Toronto: Transformations in a City and its Region, published by UPenn Press.

A Short History of Old Toronto

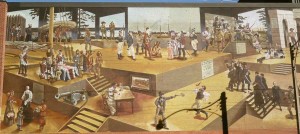

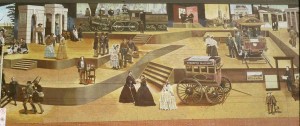

This mural on the Toronto Sun newspaper building on Front Street in downtown summarizes the history of the city from the era of fur traders to electric streetcars. I haven’t deciphered it all but it also includes events such as the Toronto Purchase, the last duel fought in the city and the introduction of electric streetcars. [Middleton, Vol 1, p. 523, claims that the first commercial electric streetcars in North America were ones that ran at the National Exhibition in Toronto in either 1883 or 1884. I don’t know whether that’s really the case, but it took almost fifteen years after that to electrify all the horse-drawn routes in the city.)

Toronto Sun Building Mural, painted in 1993 for the bicentennial of the founding of Toronto. Voyageurs and the signing of the Toronto Purchase are on the left, the American invasion during the War of 1812 is top right of the left photo, the first steam railway engine built in Canada is top centre of the right photo, horse drawn and electric streetcars are on the right.

I had to take the mural in two photos, which coincidentally reflect my understanding of the main periods in the city’s early history. From 1793 to about 1850 (the mural photo on the left) it was a colonial backwater, and from 1850 until 1940 it grew into an industrial manufacturing city, still very provincial but nonetheless the second largest city in Canada after Montreal.

[Incidentally, some of all of the illustrations I use here were acquired over several decades for my teaching and I have lost track of their provenances, but I am grateful to the sources wherever they may be.]

Toronto before 1850

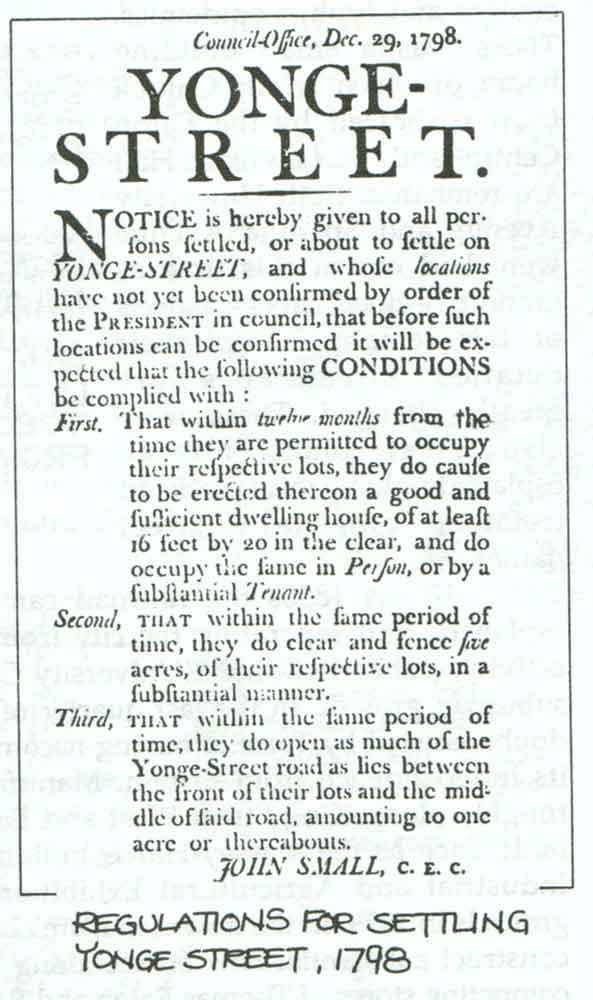

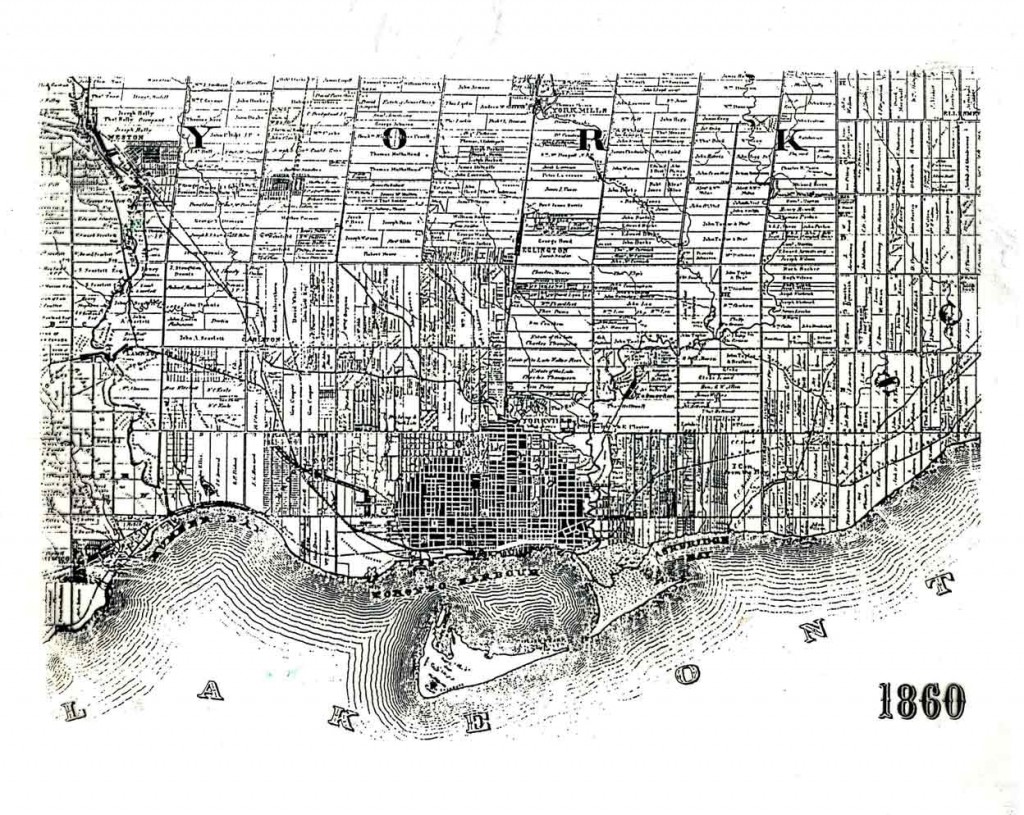

Only a handful of buildings and no streetscapes from before 1850 remain. What has endured is the grid survey, begun modestly before 1793, and immediately reinforced when Simcoe arrived. Its impact is very clear in the map of Toronto in 1860 shown below. Queen Street was the original base line for the survey, with Yonge Street aligned perpendicularly to it as a settlement road and a future trading route that would lead to Lake Huron. (There’s a great account of the origins and subsequent history of Queen Street here.)

Only a handful of buildings and no streetscapes from before 1850 remain. What has endured is the grid survey, begun modestly before 1793, and immediately reinforced when Simcoe arrived. Its impact is very clear in the map of Toronto in 1860 shown below. Queen Street was the original base line for the survey, with Yonge Street aligned perpendicularly to it as a settlement road and a future trading route that would lead to Lake Huron. (There’s a great account of the origins and subsequent history of Queen Street here.)

The grid survey has a standardized regularity – roads about 1.25 miles apart (which had to be cleared by the settlers, as the Yonge Street notice indicates) permitted settlement of the region on farms of 100 acres each. This regular rectangularity has had an enormous impact on the current urban structure of the entire region, especially in the old city where it is the prevailing street pattern, but also as a mega-grid of what were originally concession and side roads that have been converted into a system of arterial roads in the inner and outer suburbs.

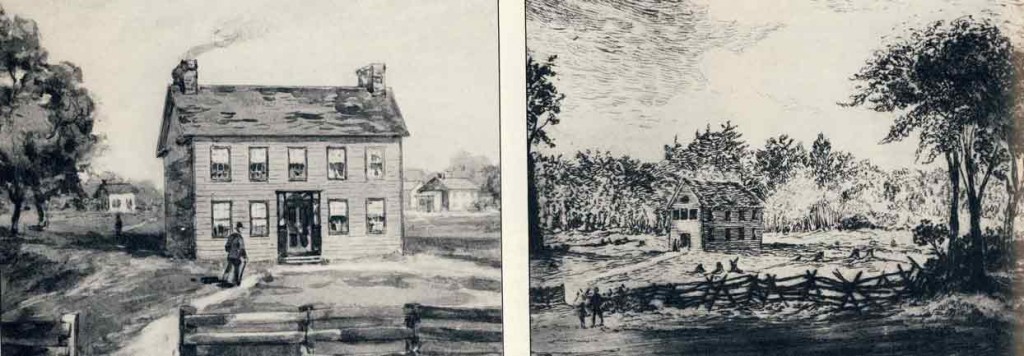

In a moment of imperial enthusiasm Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe changed the name of Toronto to York three weeks after he first landed here to establish it as the capital for Upper Canada. For several decades the Town of York was very remote and consisted of little more than scattered houses in forest clearings with a couple of commercial streets. It had few trappings of civilization and most visitors were profoundly unimpressed. The name was changed back to Toronto in 1834, and at the same time it was incorporated as a city.

Buildings in the Town of York about 1810 when it consisted of little more than a few houses in clearings in the forest. Things didn’t change much for the next twenty years

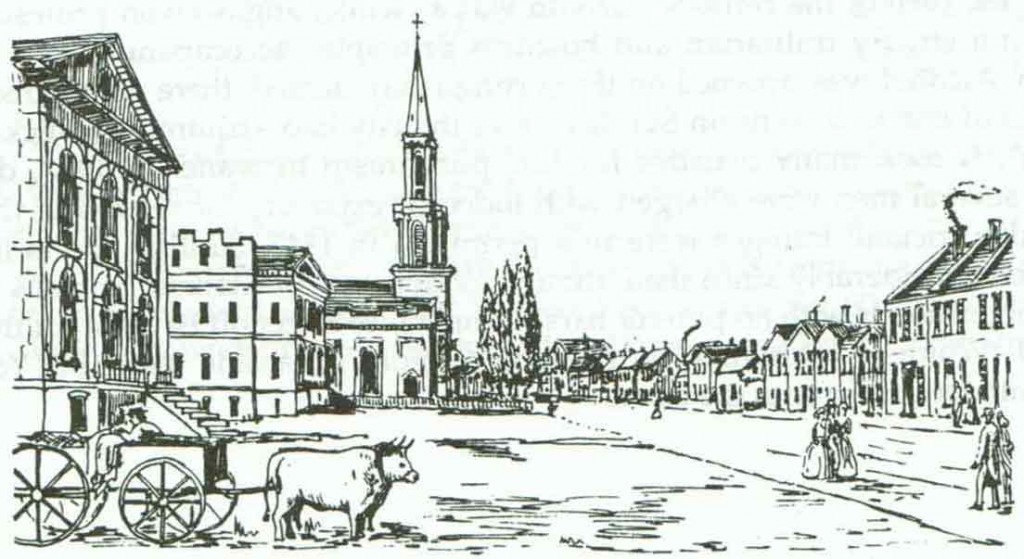

KIng Street in 1835 showing the Court House and St James Cathedral on the left. (This is my drawing based on a contemporary engraving)

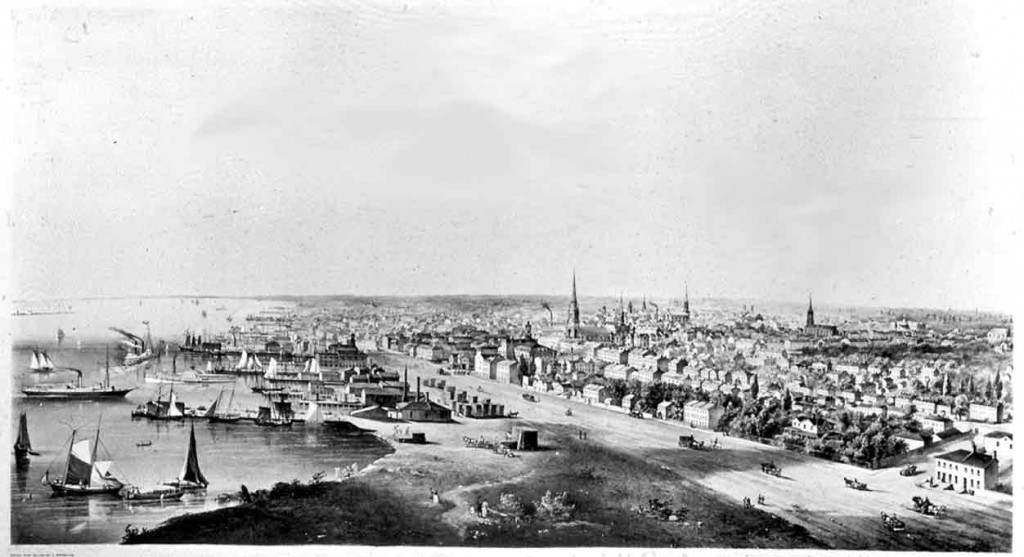

In 1850 Toronto was still a remote government and market town, a small city of church spires surrounded by farms. Roads, such as Yonge Street, Kingston Road and Dundas Street, ran out of the city but, except in winter when sleighs could be used, they were rough, uneven and exceedingly slow. The easiest connections to the outside world were by ship on Lake Ontario.

A bird’s-eye view of Toronto about 1850, shortly before the railways arrived and when it was still a city of spires and sailings ships. The wide road near the lakefront was the Esplanade. Plans to turn it into a formal promenade were thwarted when the railway was run along it 1852 or 1853, effectively cutting off the city from the lake.

Toronto’s growth as an unplanned industrial, streetcar city

Until 1840 Toronto’s growth was slow, and mostly involved cutting down trees, removing the stumps, building mills, establishing small farming communities and putting up churches and a few government and other institutional buildings. Most manufactured goods had to be imported. In the 1840s things picked up a bit – gas lights were introduced, a telegraph line to Buffalo was built – and after the first railways were constructed in 1852 and 1853 the pace of change increased dramatically, import replacement became common and Toronto became a centre of industry, with factories lining the railways and the lakefront.

Toronto in 1860, a few years after the first railways had been built. Built-up areas are black, everything else was farms. The rail lines can be seen cutting diagonally across the grid and, in the city, along the lakeshore where Union Station was located. The northern edge of the built-up area was Bloor Street, and the small town of Weston, founded only a few years after Toronto and now a centre within the inner suburbs, is in the north-west corner. The dominance of the grid is clear; it tilts north-east at St Clair Avenue because Simcoe had found an easier route to Georgian Bay on Lake Huron (via Lake Simcoe) shortly after the initial survey in 1793, and reoriented Yonge Street to take advantage of this.

In addition to promoting industrial development the railway had two long-term effects. Even though most factories have now closed or moved away, industrial areas next to the railway lines persist as zones of relatively low income. And the railway effectively cut off the city from the lakefront, a problem which only now is being resolved. The photo on the left I took looking east from the CN Tower about 1980 and shows the broad swath of rail lines running into Union Station which the streets cross in ugly tunnels. Construction of the Gardiner Expressway (just right of the railway) in the 1950s reinforced the separation of city and lake; to the right of that were industrial uses on landfill. The orange building in the top centre is the first phase of the St; Lawrence Neighbourhood; the Port of Toronto is top right, with mouth of the Don River.

In addition to promoting industrial development the railway had two long-term effects. Even though most factories have now closed or moved away, industrial areas next to the railway lines persist as zones of relatively low income. And the railway effectively cut off the city from the lakefront, a problem which only now is being resolved. The photo on the left I took looking east from the CN Tower about 1980 and shows the broad swath of rail lines running into Union Station which the streets cross in ugly tunnels. Construction of the Gardiner Expressway (just right of the railway) in the 1950s reinforced the separation of city and lake; to the right of that were industrial uses on landfill. The orange building in the top centre is the first phase of the St; Lawrence Neighbourhood; the Port of Toronto is top right, with mouth of the Don River.

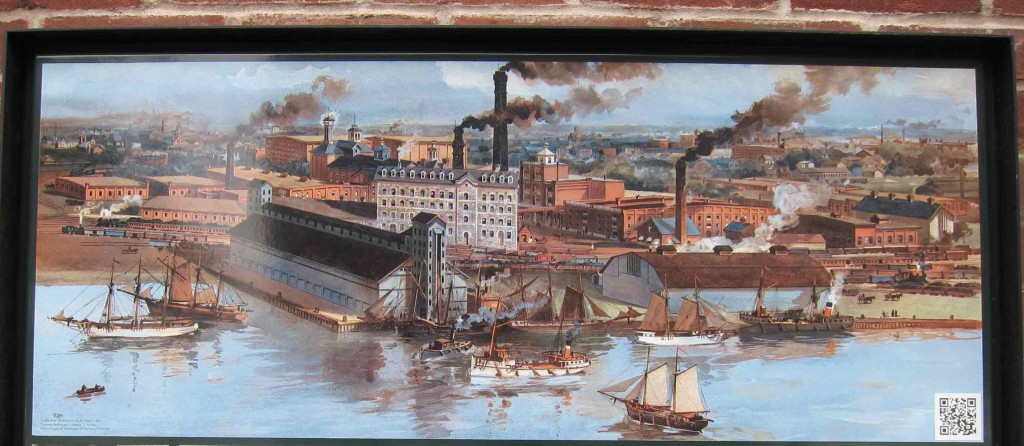

By the 1880s Toronto was manifestly an industrial city, a fact celebrated in contemporary images of smoking factory chimneys which symbolized prosperity and progress.

Toronto in the 1880s – a city of chimneys. This is a photo of the sign outside Gooderham and Worts distillery, now the Distillery District – a pedestrianized heritage and tourist area just east of downtown.

With industrialization came global dreams that foreshadowed Toronto’s current status as a world city. For instance, Massey-Harris, a manufacturer of farm equipment that had begun in the town of Brantford about 100 miles west of Toronto and had opened a large factory next to the rail lines on King Street west of downtown Toronto, saw itself as helping to feed the world. This photo of a poster from the 1880s (I think I took it at the Halton Museum of Rural Life) celebrates Canada’s role as the breadbasket of the old and new worlds and shows more factories with smoking chimneys. The Toronto factory, shown top right, is now the site of a large condominium development.

With industrialization came global dreams that foreshadowed Toronto’s current status as a world city. For instance, Massey-Harris, a manufacturer of farm equipment that had begun in the town of Brantford about 100 miles west of Toronto and had opened a large factory next to the rail lines on King Street west of downtown Toronto, saw itself as helping to feed the world. This photo of a poster from the 1880s (I think I took it at the Halton Museum of Rural Life) celebrates Canada’s role as the breadbasket of the old and new worlds and shows more factories with smoking chimneys. The Toronto factory, shown top right, is now the site of a large condominium development.

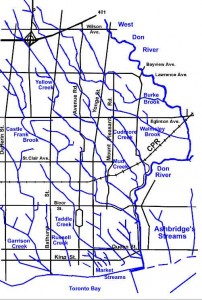

Industrialization and urban growth came at a local price. There was air pollution from the smoke, of course, and the rivers and lake were used for waste disposal and became seriously polluted. There was an absence of planning as we might understand it, but the city grew in a sort of orderly fashion imposed by the grid street system. This was achieved in part by filling in and building over numerous creeks and watercourses, something which made possible the high population densities that continue to make streetcars viable. In the last decade of the century the lower section of the Don River was straightened in an attempt to improve flow, flush out pollution, and enlarge the port. The valley of the lower Don has since become a sort of grand utility corridor, with an expressway, a railway, and hydro, gas, oil and sewer lines. Nevertheless, much of the pollution has now been mitigated and there are plans to re-naturalize the mouth of the Don.

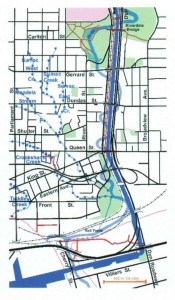

A map from Lost Rivers showing the original meanders of the lower Don River that were removed when it was made into a channel.

A map of the watercourses in central Toronto from Lost Rivers. Many of them, such as Garrison Creek and Taddle Creek, are buried. The Don River is on the right.

As new factories provided jobs, the population grew. In the absence of any regulations preventing it, some residential areas were built right next to factories, and though the worst examples of this have disappeared a few examples remain. However, much of the new housing was in areas near horse-drawn streetcar routes, and in the 1880s and 90s many streets of distinctive brick bay-and-gable houses were constructed (a by-law passed following a destructive fire in the 1830s prohibited construction of wood houses). Porches, often with classical revival columns were often added a decade or so later.

Houses next to old factories in the Niagara district, photo taken about 1985. This sort of juxtaposition of land uses predates zoning regulations.

Bay and gable houses built in the 1880s in Cabbagetown. On the left the houses are unmodified, and on the right are two renovated ones with porches removed, new windows and brick cladding, and fenced front yards – all signs of gentrification.

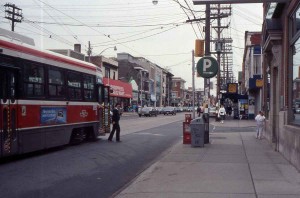

The city grew, albeit slowly, in association with horse-drawn streetcars, particularly in the 1880s and 90s. Long main streets almost continuously lined with two and three storey commercial buildings – shops below and apartment above – developed along the streetcar routes. With electrification these were simply extended. The old city of Toronto is mostly built around this extensive grid of retail streets, an urban form that has proved to be very adaptable to changing economic and social conditions and is an important factor in the present-day vitality of the old city’s streets. The main exceptions to the grid of the streetcar city were affluent residential areas, where the residents presumably had their own carriages or cars and did not ride streetcars, and many residential streets are picturesquely curved.

Queen Street East – a commercial main street along a streetcar route line with commercial buildings. Photo taken about 1990.

Houses on a curving street in the affluent suburb of Rosedale – laid out in the late 19th century and developed from then until the 1930s.

Downtowns, as we think of them now, were an invention of the second half of the 19th century. In part this was because the telegraph and telephones allowed administrative offices to be separated from factories. Toronto’s downtown was concentrated around King Street, Queen Street and Yonge, where there were department stores, clubs for businessmen, theatres, opera houses and restaurants. Downtown has subsequently drifted a few blocks west but many of the original amenities remain in this part of the city.

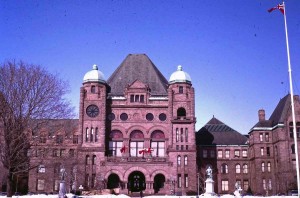

Both provincial and city governments contributed directly to the development of the central city. In the 1890s the Province of Ontario constructed a massive, romanesque, sandstone legislature in the middle of Queen’s Park which is one of the few deviations from the grid. It is a sort of circle that was originally the site of King’s College, the predecessor of the University of Toronto, founded in 1828 and located at the northern end of what is now called University Avenue, and was then a private, gated park, twice the width of other streets, used for recreational strolling and riding. In 1859 the University leased much of the land to the City of Toronto for 999 years to create the first municipal park in British North America, and moved its campus a few hundred yards to the west, where it arranged colleges around another roughly circular open space. In the 1880s the southern part of Queen’s Park was given to the Province to build the legislature. The Royal Ontario Museum, which is just north of Queen’s Park, has a good account of this history, with maps. At about the same time the city built itself a Richardsonian-Romanesque city hall at Bay and Queen (now in use as a court house). This were really the last gasps of this sort of ornate and decorated architecture. Perhaps because of changes in architectural fashions, or perhaps because the costs of the skilled labour required to make them became too high, since the beginning of the 20th century buildings buildings have had much less decorative detail.

The Ontario Legislature in Queen’s Park – statues of notable politicians (and the one of Queen Victoria in the book) are in front. This was taken in the 1980s when the building was less obscured by trees than it is now.

Carvings on a capital adjacent to the main doorway of Old City Hall. The character with the moustache is a likeness of the architect, E.J.Lennox.

Streetcar suburbs and growth in the early 20th century

After 1900 the city continued to expand in relation to streetcar lines, all now electrified, but the streetcar houses were much less ornate than their 1880s forebears. The boxy houses on the left below are in North Toronto and were built in the 1920s near the Yonge streetcar line (the larger house on the street corner is a fourplex apartment, common for corner lots in this district); these predated widespread car ownership and have mutual driveways, now converted to front-yard parking. The semi-detached houses front onto the Gerrard line east of the Don River, and were probably built around 1912. Both had rear lane-ways that were used for deliveries, an urban form that has been copied in new urbanist developments.

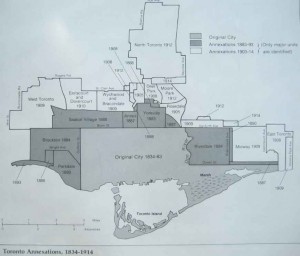

As it had grown since 1834 the built up area of Toronto had continually spread into adjacent smaller municipalities and the city had systematically annexed them (including the area of North Toronto where the streetcars houses in the photo above are located), so the area of the incorporated City had kept pace with growth. The names of many of the old municipalities have been preserved in business improvement areas, and, for example, Main Street subway station refers to the main street of East Toronto. In 1912 the City was given authority to control subdivision in adjacent municipalities in order to prevent unserviced developments that might try to piggy-back on city services, and there were no more annexations until some further rationalization occurred under Metro Toronto in the 1960s (the annexation of Forest Hill and Swansea, for example).

Annexations by the City of Toronto from 1834 to 1914, when it had pretty well assumed the shape it was to have until it disappeared as a municipality in the imposed amalgamation with adjacent municipalities in 1998.

In the first three decades of the 20th century the city maintained its manufacturing industries and continued to develop as a financial centre that was beginning to challenge Montreal. Financial businesses concentrated along Bay Street, shown below in the 1920s. In 1931 the Bank of Commerce completed a 34 storey skyscraper, the tallest in the British Commonwealth until the 1960s.

Bay Street, the heart of Toronto’s financial district, in the 1920s. Old City Hall terminates the view. Bay Street remains the symbolic centre of Canada’s financial industry, and this specific view has scarcely changed except for types of cars and no streetcars.

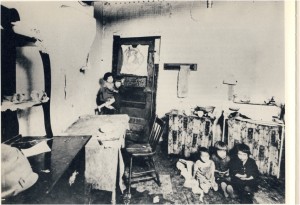

Not everybody participated in this prosperity. For some there were harsh labour conditions, especially in the garment industry that was concentrated along Spadina Avenue which was a major Canadian centre for the organization of unions. (Incidentally “Mapping Our Work: Toronto Labour History Walking Tours” has an excellent account of the history of central Toronto, based on buildings and monuments, from the perspective of those who made it.) In the years before World War I unplanned, or self-built suburbs were built at the ends of several of the street car lines, owners adding bits to their houses when they had time and money. Many of these houses remain, though they have been updated and have gardens and trees, so they are no longer as stark or obvious as they were originally. The area now occupied by hospitals on University Avenue was a slum without water or sewage until the first hospitals relocated there just before World War 1. Another area of slums a few blocks east of downtown was identified in the 1930s, and was replaced after World War 2 by the modernist social housing project of Regent Park.

Housing conditions in the 1930s in the area that was to be replaced by the modernist housing project of Regent Park about 1950.

At the edge of the city many roads remained unpaved well into the 1920s and 1930s. Even if people had cars they were unreliable and the roads could turn into muddy traps in spring or summer thunderstorms. Radial railways (interurbans) were more smoother and more reliable; lines were built along Yonge to Lake Simcoe, along Kingston Road to West Hill, and out to Guelph, providing fast and smooth travel across the Toronto region. But radial lines were short-lived. As highways were paved and car ownership increased they became unprofitable and all had been were closed down by the mid 1930s. The only indications of them now are a few convenience stores named for stops.

The decline of the radial lines anticipated the rise of the new transportation technology of the expressway. In 1939 the Queen Elizabeth Way, the first limited access, intercity highway in North America that ran from Toronto to Niagara Falls was opened. Streetcars continue to be a key element of the transit system in old Toronto, but since then they have not been a formative element in shaping the city and the metropolitan area has expanded around expressways and highways.

The Queen Elizabeth Way shortly after it was opened in 1939 – starkly modern and unlike all previous roads just for motor vehicles.