This page is part of the companion website to my book Toronto: Transformations in a City and its Region, published by UPenn Press.

This page is part of the companion website to my book Toronto: Transformations in a City and its Region, published by UPenn Press.

Toronto in Wartime

Almost all the evidence of the changes made to Toronto during World War 2 has disappeared. The munitions plants were converted to peacetime uses, and the yard for making minesweepers dismantled (there are some photos in the shopping mall at Queen’s Quay). The town of Ajax has retained its name (the history of the munitions plant at Ajax is available here under the DIL Years), and there are a few areas of distinctive housing built for workers in wartime industries and a sign for Intrepid Park at the site of Camp X, the training facility for spies where Ian Fleming spent some time.

Wartime housing in Malton, probably built for workers at the Lancaster bomber plant. Areas of similar housing were built in East York and Etobicoke. And the sign for Intrepid Park on the Waterfront Trail in Ajax.

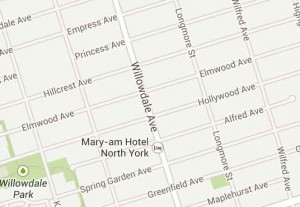

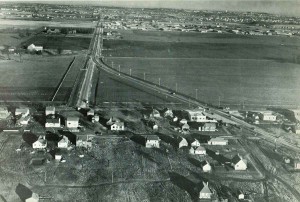

Suburban developments in the first few years after the war were mostly of small brick houses of 1000 square feet or less, often not much larger than the emergency wartime houses and with many features roughed in and to be finished by the new owners. These were on street grids, such as this one in the Willowdale area of North York, that presumably had been laid out before the war, but the driveways show that these houses were intended for cars rather than streetcars.

The 1943 Plan for the Metropolitan Area of Toronto

Here are two versions of the plan for post-war development of Toronto, discussed in my book, that had no official status, yet proved to be enormously influential as different elements were implemented over the next 25 years.

This black and white version (illustrated, for example, in Jim Lemon, Toronto since 1918: an illustrated history), clearly shows the proposed grid of expressways or superhighways imagined by the City Planning Board. The Queen Elizabeth Way had already been built and some, such as Superhighway A (the Gardiner Expressway) and Superhighway D (Highway 401), were subsequently constructed. Most of the others, such as a proposed sunken expressway running along Bloor Street, fortunately were not. Several proposed industrial areas were at the time munitions plants later converted to other industrial uses. The inner greenbelt consisted mostly of the Humber and Don river valleys; these were protected from all development following a major flood in 1954, though the proposed parkway was built down the eastern branch of the Don valley. The 1943 Plan also included an outer greenbelt, essentially the Oak Ridges Moraine, which has been implemented since 2006. Most areas of late-Victorian housing are shown as “residential redevelopment” areas, but this never happened; the model public housing area (the small cross-hatched block east of downtown) had been identified in the 1930s as slums and this was redeveloped n the 1950s and 60s as Regent Park social housing project. The bucolic village green symbols for proposed suburban residential developments suggests that they were imagined as garden cities but were actually built up as suburban subdivisions. Malton Airport has become the Lester B. Pearson International Airport.

This colour version of the 1943 Plan I have taken from Richard White The Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe in Historical Perspective (Toronto: Neptis Foundation, 2007). It also shows the grid of expressways, industrial areas, and proposed suburban developments (and the grid of the Willowdale area discussed in the previous section, even though it had not been built up at that time). But unlike the black and white version it also shows proposed subway lines, some running along the centre of expressways (as became the case with the Spadina Line). It also includes a proposed subway running from the eastern part of the city along Queen Street, part of which has been under discussion in 2013 as the so-called Downtown Relief Line. It is interesting that commercial airports, agricultural areas and parks are regarded as a single category – not how we view them now.

These maps correspond closely to the area of what was to become Metropolitan Toronto, though at that time there had been no discussion of this possibility.

Signs at the edge of Don Mills claim it is “Canada’s First Planned Community.” Probably not. Richard Harris in his 2004 book Creeping Conformity: How Canada became Suburban 1900-1960, claims that Westdale in Hamilton was a precursor as a large, developer controlled subdivision. In fact, the practices used in Don Mills, such as curving streets, culs-de-sac, and neighbourhood units, were widely used across North America and internationally (e.g. in British new towns and Canberra, Australia) in the 1950s and 60s, and in Toronto there were precedents for the types of houses (in previous post-war development) and low-rise apartment buildings (along streetcar routes in the old city). But a historical plaque at central intersection of arterial roads in Don Mills claims that it “has been imitated in suburban development across Canada,” and that does have some justification. It was certainly imitated in the Toronto region.

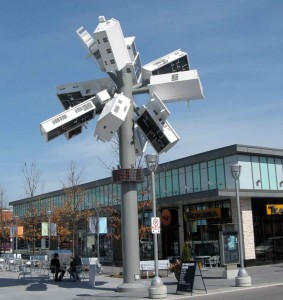

Four storey apartments at the centre of Don Mills, and an installation of typical Don Mills houses by Douglas Coupland (of Generation X renown) in the recently remodelled Don Mills plaza

But there were also many new details, including the modernist architectural styles of some of the industrial and institutional buildings. An excellent online tour of Don Mills, describes most of these innovations. Above all, the urban form broke with previous practices in the city – houses arranged on curving streets around elementary schools, and the large cluster of almost fifty low apartment blocks in the circle road around the central intersection (all very apparent in the map in my book). And there is no question that Don Mills had a significant local impact on suburban development. For instance, the photo below of a 1980s development on Pharmacy Ave in north Scarborough shows a variant of the circle around an apartment cluster introduced in Don Mills, surrounded by single family houses on P-loops and U-loops arranged in neighbourhood units.

Flemingdon Park is the area immediately south of Don Mills, (discussed in Chapter 5 of my book as the origin of the high-rise apartment boom in Toronto). It was planned as private residential area, mostly rental, by the same person – Macklin Hancock – who had planned Don Mills. But in Flemingdon Park low-rise housing consists of a town-houses rather than detached houses and the apartment blocks were more or less turned on their ends to make 14 storey slabs. These were the first high-rise suburban apartments in Toronto, the beginning of a skyscraper apartment boom that continues to this day.

On the left are some early slab apartments at Flemingdon Park. The photo on the right shows a more recent point block, portables at the elementary school in the centre of the neighbourhood which are an indication of the young population profile, and signs for after school programs and ESL classes that reveal something about the social characteristics of Flemingdon as a low income area with many recent immigrants.

Metro Toronto

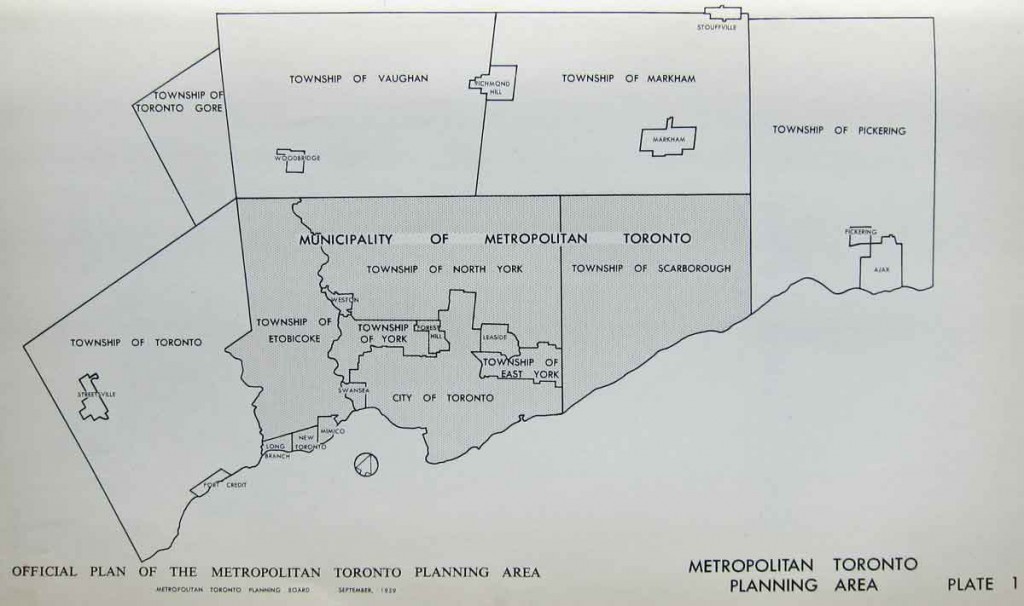

Metro, set up by the province in 1953, was a clever variation on Toronto’s former practice of annexing adjacent municipalities to deal with urban growth, but instead of being annexed they were incorporated into an overarching regional municipality that could control new development.

In this map Metro proper is the shaded area. The City had had control over subdivisions beyond its boundaries since 1912, and a similar responsibility was extended to Metro in order to ensure efficient servicing of new developments, so its planning area (the unshaded areas) was substantially larger than its political area as this map (taken from the 1959 Draft Official Plan) shows. Metro was, in effect, responsible for planning throughout the urban region.

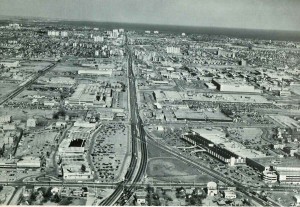

Metro guided growth and change in Toronto for almost two decades, a period of dramatic transformation because new developments were both extensive and automobile-oriented rather than streetcar-oriented. The scale of that change is apparent in these before and after air photos of the Golden Mile (along Eglinton Ave East in Scarborough; the wye of the roads gives a clear point of reference). In 1949 there were fields and a few small houses; the buildings in the distance were part of a wartime munitions plant. In 1969 everything had been built up; the plaza visited by the Queen in 1959 is bottom left, a shopping mall is bottom right, beyond that the munitions factory had been converted to a GM van painting plant, in the distance are slab apartments, subdivisions and Lake Ontario.

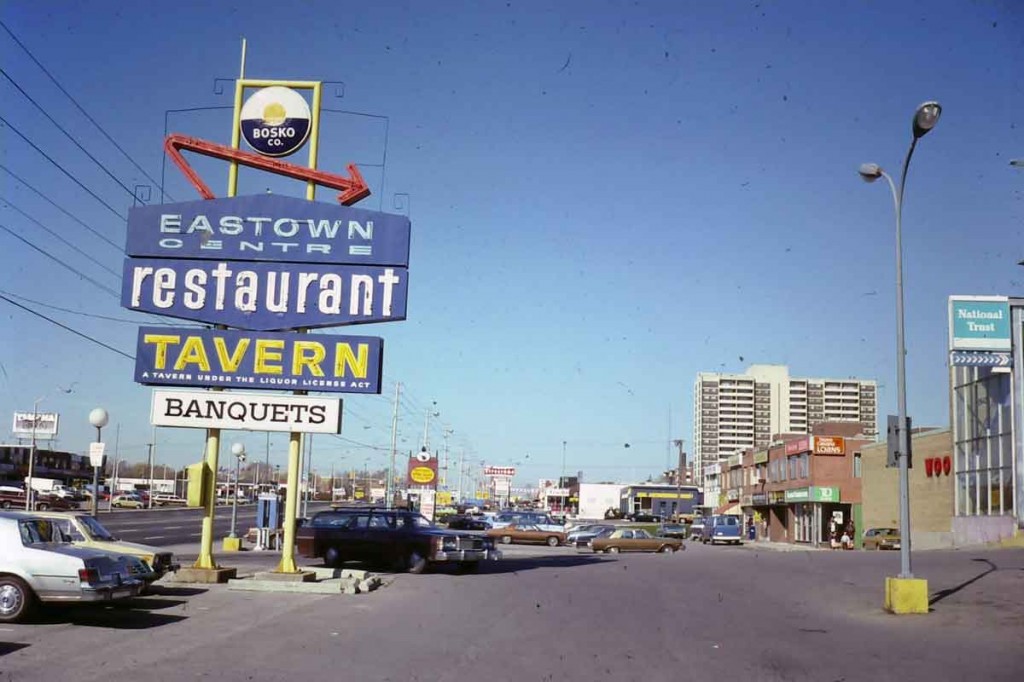

Metro systematically developed a grid of arterial roads along the concession and side roads that had been laid out 150 years before. Many of these became commercial strips, similar to the one shown below, utterly unlike the main streets that had been made before World War 2, with generous parking backed by one or two storey commercial buildings. Residential areas were arranged in neighbourhood units, some following the Don Mills model, and consisted of a mixture of single family houses, such as backsplits,around elementary schools, and clusters of slab apartments, usually close to a neighborhood shopping plaza.

Commercial Strip in Scarborough, about 1978, with two storey commercial buildings set well back from the street and dramatic signs.

Typical backsplits (one storey in front and two behind) from the 1960s, and a cluster of slab apartments from the same era, both in Scarborough.

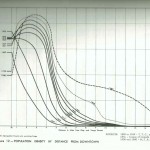

Metro not only managed suburban expansion but in and around the city centre it had the clout to implement major projects proposed in the 1943 plan, such as construction of the Yonge and Bloor subway lines, the Gardiner expressway and the Don Valley Parkway. Although the landscapes produced on Metro’s watch tended always to be utilitarian, the scope of Metro’s planning was remarkable. The diagrams and maps below (from Metro’s 1959 Draft Official Plan) indicate Metro’s aim to raise suburban densities (especially by constructing apartments and with the intention of supporting public transit systems), provide an assessment of the problems associated with the volumes of transit travel into downtown, show an ambitious expressway plan that echoes the superhighway grid of the 1943 plan, and include a proposal for a regional plan from Oshawa to Hamilton (a region for which Metro had at best partial authority) that suggested keeping urbanization close to Lake Ontario in order to avoid the high costs of installing sewerage and water systems to the north.

- Density decline from downtown

- Monocentric Toronto – transit volumes into downtown

- Metro Toronto Expressway Plan. I have marked those that were not built.

- Metro Toronto plan for region

- Queen Elizabeth visits the Golden Mile, 1959

- Bellamy Road, Scarborough

The fact that public officials, and perhaps most Torontonians, were proud of the carefully managed, automobile oriented growth was demonstrated when the Queen was taken to visit the Golden Mile during her visit to Toronto in 1959. The portly gentleman to her left is Fred Gardiner, the first chairman of Metro for whom the Gardiner Expressway was named. Under Metro’s guidance the urban area unfurled outwards, with very little leapfrogging, and by 1970 the area of Metro was mostly built-up. This was before heritage was considered important and most small villages and crossroad hamlets disappeared to make way for subdivisions and commercial strips. But there are some reminders of lost places and dreams. Bellamy Road is named for Edward Bellamy, author of the 1890 utopian novel Looking Backward, which spawned numerous societies dedicated to making “nationalist” communities that corresponded to his vision (and influenced Ebenezer Howard and the garden city movement); there was a short-lived proposal about 1900 to make a nationalist community here; nothing came of it except an enduring street name.

Renewal and Modernism

Modernism came to Toronto via Don Mills, plus the design of blocky apartment buildings, social housing urban renewal projects and New City Hall. The photo on the left shows a bit of old Toronto (the late-Victorian Avion House pub has a Men’s Room entrance on the corner; Ladies and Escorts had a separate door) and fragments of the new – the apartment towers in the centre and on the right the boxy, undecorated red-brick apartments of the Regent Park social housing project (the model housing area identified in the 1943 plan). Regent Park, built in the 1950s, was a clean-sweep (it erased whatever preceded it), superblock renewal project that in the best modernist manner arranged the new buildings in ways that were unrelated to streets; Alexandra Park, built in the 1960s just west of downtown (and now converted into the Atkinson Coops), was less aggressive and did preserve some streets and old buildings that were renovated and incorporated into the project,

Modernism came to Toronto via Don Mills, plus the design of blocky apartment buildings, social housing urban renewal projects and New City Hall. The photo on the left shows a bit of old Toronto (the late-Victorian Avion House pub has a Men’s Room entrance on the corner; Ladies and Escorts had a separate door) and fragments of the new – the apartment towers in the centre and on the right the boxy, undecorated red-brick apartments of the Regent Park social housing project (the model housing area identified in the 1943 plan). Regent Park, built in the 1950s, was a clean-sweep (it erased whatever preceded it), superblock renewal project that in the best modernist manner arranged the new buildings in ways that were unrelated to streets; Alexandra Park, built in the 1960s just west of downtown (and now converted into the Atkinson Coops), was less aggressive and did preserve some streets and old buildings that were renovated and incorporated into the project,

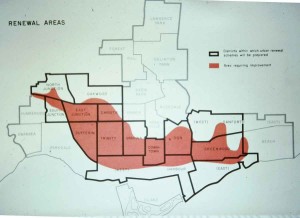

Plans to redevelop or renew most of the central city with clean-sweep projects (suggested in the 1943 plan) remained on the books until the late 1960s. The thinking was that anything old (such as late-19th century bay and gable houses) should be renewed to look like Regent Park or Alexandra Park. This fate was probably avoided mainly because Metro’s funds were being directed to other projects, most of them in the rapidly growing suburbs.

Urban renewal areas proposed in the 1968 City of Toronto Official Plan included the CBD and almost all the areas of Victorian bay and gable houses that have subsequently been gentrified.

But in the downtown core in the 1960s things happened differently. Here there were both the will and the money for renewal. New City Hall was regarded as a symbol of Toronto’s modernization, and unlike the social housing projects its modernity has not diminished and it remains a vital landmark in central Toronto. At about the same time the Toronto Dominion Centre with the first modernist skyscraper offices in the city were constructed. Both projects involved the demolition of entire city blocks but there was little consternation about this. They also both offered ways of separating pedestrians from streets – City Hall with raised walkways and the Toronto Dominion Centre with tunnels lined with shops. The walkways remain as a sort of folly around City Hall, but the tunnels have won out and now stretch into a maze of over 27 kilometres, officially called The Path and said to be the largest underground retail area in the world. I confess that I don’t find much of The Path inspiring – mostly a shopping mall with low ceilings – but a map of it is available here. To get into City Hall from it you have to leave the tunnels and follow a yellow striped path through an underground parking lot.

The former observation level of the Toronto Dominion centre provided a splendid view of New City Hall. This photo was taken from it in 1971 and shows some commercial skyscrapers along University Avenue on the left, Old City Hall and a bit of the new Simpsons Tower on the bottom right, and high-rise apartment slabs in the distance. The photo on the right, I took in the 1990s and shows the walkways around Nathan Phillips Square in front of New City Hall (just visible on the right of this photo). The walkways are open to the elements, would have been very difficult to keep clear of snow in winter and do not comply with modern universal design standards because they are accessible only by stairs.

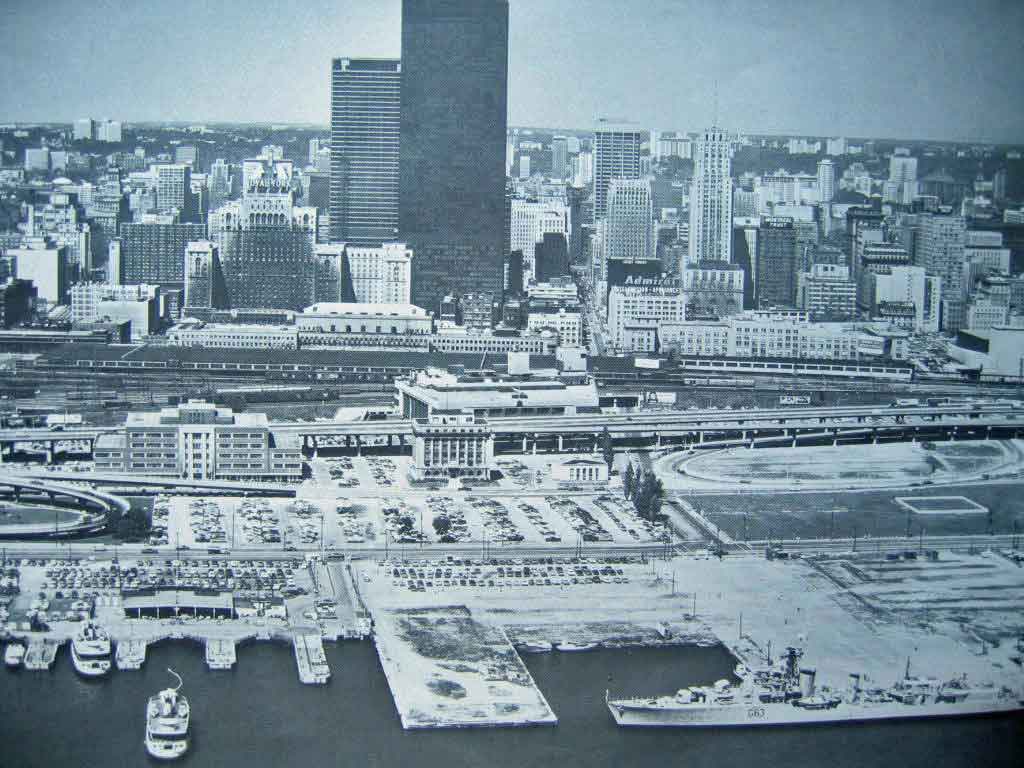

The downtown skyline in 1969 was dominated by the two towers of the Toronto Dominion Centre, designed by Mies van der Rohe. The Royal York Hotel is just in front of them to the left, and the 1930 Bank of Commerce building is the slender tower to the right. Rail lines and the Gardiner Expressway (and parking lots) separate downtown from the waterfront. The old City was on the brink of another transformation in which Metro’s influence would be diminished, though suburban growth and, after a short pause, renewal of the financial district continued unabated.