This page is part of the companion website to my book Toronto: Transformations in a City and its Region, published by UPenn Press.

This page is part of the companion website to my book Toronto: Transformations in a City and its Region, published by UPenn Press.

The End of Metro’s Modernism

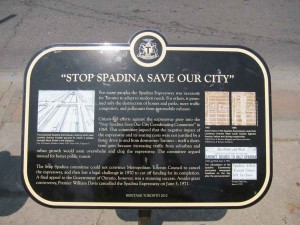

Toronto didn’t experience the urban crisis of the late 60s associated with the Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam War protests in the U.S., but there were some profound changes between about 1969 and 1976 that put an effective end to Metro’s approach of out-with-the-old/in-with-the-new. One of first, and probably the best known, was the successful Stop Spadina movement that prevented the completion of an expressway, shown on the 1943 plan, that would have run into the heart of the city through some streetcar neighbourhoods. It marked the end of expressway construction in Metro and was turning point in Toronto’s development. In itself this was not exceptional; protests in a number of cities in America and other countries also stopped expressway construction. But in Toronto the indirect effect seems to have been to create an awareness of the value of main streets and dense residential areas of the streetcar city, which hitherto had been taken for granted, and from that came the beginnings of revitalization of the old City that continues to this day.

This heritage plaque at the corner of Bloor and Spadina acknowledges the role of the “Stop Spadina” movement in preventing the completion of the proposed expressway which would have debouched in the central city near the University of Toronto. The photo above at the right shows the section that was built in the north-west past of the city, with a subway running down the middle as suggested in the 1943 plan, and is now called Allen Road.  Toronto was also affected by several other more or less simultaneous changes that were occurring in many other cities, for instance, deindustrialization, which has continued in various manifestations up to the present day. The photo on the right, taken about 1995 of a turn of the century industrial area to the west of downtown, shows an adaptive reuse of a former factory at a time when anti-smoking by-laws were just beginning to be implemented. For a number of reasons, some of which are discussed below, deindustrialization did not lead to the city centre and old industrial areas of Toronto emptying out in the ways that happened in some American rust-belt cities.

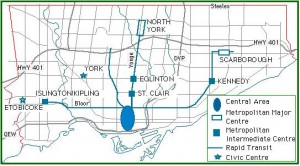

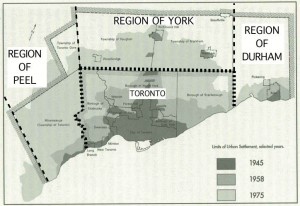

Toronto was also affected by several other more or less simultaneous changes that were occurring in many other cities, for instance, deindustrialization, which has continued in various manifestations up to the present day. The photo on the right, taken about 1995 of a turn of the century industrial area to the west of downtown, shows an adaptive reuse of a former factory at a time when anti-smoking by-laws were just beginning to be implemented. For a number of reasons, some of which are discussed below, deindustrialization did not lead to the city centre and old industrial areas of Toronto emptying out in the ways that happened in some American rust-belt cities.  A major change within Metro in the 1970s was the development of a ‘deconcentration’ policy, intended to reduce congestion in the downtown core and on transit into the core. This illustration is based on a map in MetroPlan1976, and shows the intermediate and other nodes for office and retail deconcentration that were proposed. In fact, several of these (such as North York and Scarborough, discussed below as Suburban Downtowns) were already being intensified. At about the same time a major change occurred beyond the boundary of Metro that was to affect the future of the city. By the early 1970s urban development had already spread across Metro’s borders, though Metro, with its extensive planning area (illustrated in the entry for Chapter 5), had control over that. But about 1975 the province decided to end this, and reorganized surrounding local municipalities into Regional Municipalities – two tier local governments with similar responsibilities to Metro – that took over over all the planning responsibilities that Metro had once had over adjacent municipalities. This effectively landlocked Metro so that it would be able to grow only by infill and intensification, not by conventional outward suburban growth. In the Regional Municipalities there is still a large supply of land for suburban growth, but Metro, and now its successor the new City of Toronto, are literally post-suburban.

A major change within Metro in the 1970s was the development of a ‘deconcentration’ policy, intended to reduce congestion in the downtown core and on transit into the core. This illustration is based on a map in MetroPlan1976, and shows the intermediate and other nodes for office and retail deconcentration that were proposed. In fact, several of these (such as North York and Scarborough, discussed below as Suburban Downtowns) were already being intensified. At about the same time a major change occurred beyond the boundary of Metro that was to affect the future of the city. By the early 1970s urban development had already spread across Metro’s borders, though Metro, with its extensive planning area (illustrated in the entry for Chapter 5), had control over that. But about 1975 the province decided to end this, and reorganized surrounding local municipalities into Regional Municipalities – two tier local governments with similar responsibilities to Metro – that took over over all the planning responsibilities that Metro had once had over adjacent municipalities. This effectively landlocked Metro so that it would be able to grow only by infill and intensification, not by conventional outward suburban growth. In the Regional Municipalities there is still a large supply of land for suburban growth, but Metro, and now its successor the new City of Toronto, are literally post-suburban.  This map shows that in 1945 the old City of Toronto was fully built-up, in 1958 Metro still had plenty of room for growth, yet by 1975 development had spread well beyond Metro’s borders. Planning for more urban expansion could have been achieved by extending Metro’s already extensive planning authority even further, but the province chose instead to reorganize surrounding areas into regional municipalities, reducing Metro’s planning responsibilities and effectively landlocking it. (If I remember correctly, I took this map from a thesis by Martin Luymes. It does exaggerate the 1975 developed area, especially in Mississauga which only now, in 2013, is close to being fully built-up, but it gives a sense of the province’s logic for creating regional municipalities. An extended Metro would have been overwhelming political presence within Ontario).

This map shows that in 1945 the old City of Toronto was fully built-up, in 1958 Metro still had plenty of room for growth, yet by 1975 development had spread well beyond Metro’s borders. Planning for more urban expansion could have been achieved by extending Metro’s already extensive planning authority even further, but the province chose instead to reorganize surrounding areas into regional municipalities, reducing Metro’s planning responsibilities and effectively landlocking it. (If I remember correctly, I took this map from a thesis by Martin Luymes. It does exaggerate the 1975 developed area, especially in Mississauga which only now, in 2013, is close to being fully built-up, but it gives a sense of the province’s logic for creating regional municipalities. An extended Metro would have been overwhelming political presence within Ontario).

Changes Downtown

With one major exception, since Stop Spadina there has been a deep inclination to protect the neighborhoods and urban qualities of the streetcar parts of the old City. The exception is the downtown core, including both the financial district and the 19th century industrial areas close to it, where a combination of office and condominium skyscrapers, and low or mid-rise residential projects have replaced much of the former cityscape.

Downtown skyline in 1974 with CN Tower under construction, Toronto Dominion Centre towers and Commerce Court as the tallest skyscrapers, and the first lakefront condominiums and hotels under construction on the right.

Downtown skyline in 2011. The Toronto Dominion Centre is barely visible in the cluster on the right. The towers to the left of the CN Tower and along the lakefront are all condominiums. The CN Tower obviously is still the most dominant feature (the Rogers Centre (former SkyDome) sports stadium is next to it) but the remarkable changes to the central city are also obvious.

The new skyscraper offices have turned streets in the financial district into canyons. The photo on the left below shows King St looking east from University Ave. The image from Google Earth on the right shows the financial district (City Hall top centre, Union Station bottom centre) and gives a sense of the concentration of office skyscrapers between University Avenue and Yonge Street, almost all built between 1970 and 1990. Office construction downtown was almost dormant between 1990 and 2010 but several new office towers have been added in the last couple of years or are under construction (including the ones at very bottom centre with clear shadows, next to the Air Canada Centre, which describe themselves as the South Financial Core).

At ground level things are not quite as bleak as these photos suggest, at least in summer. There are some smalls parks and plazas that are well used, such as this one in between the Toronto Dominion Centre towers (this photo I took in the 1980s). In winter they are, of course, less appealing and then the retail tunnels of the Path come into their own. These link into the Eaton Centre, a block long enclosed shopping mall adjacent to Yonge Street north of Queen, built in the 1970s, shown on the right. I took this photo in 1978; it hasn’t changed much (the birds are an installation of Canada Geese by artist Michael Snow).

Another type of renewal – typified by the low-rise and mid-rise residential project of St Lawrence Neighbourhood – has occurred in areas of the inner city close to the CBD. The view on the left below shows a street of townhouses in the original part of St.Lawrence, with co-op apartments in the background. This is in the centre-right block in the photo on the right, taken in 2010 from the Scotia Plaza skyscraper. The green strip is Crombie Park, named after a former and popular mayor, on the line of the waterfront Esplanade that was planned in 1850 and abandoned when the first railway was built. The large shed just left of centre is St. Lawrence Market, and both above and to the right of that are other new residential developments. The Port of Toronto at the artificial mouth of the Don River is top right.

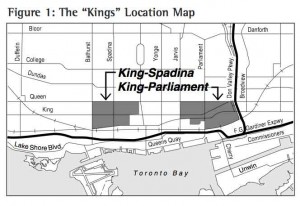

A more recent stimulus to redevelopment in the central city came with the dezoning of the two Kings (the areas of King-Parliament Street and King-Spadina Avenue to the east and west of downtown respectively) in the 1990s, which removed land-use restrictions on former industrial and commercial areas, and has led to a still-continuing boom in high-rise condominium construction (the planning process is summarized in a City of Toronto report here).

These condominium towers are rapidly changing the skyline and the streets of the central city. The first ones constructed in the late 1990s were under 20 storeys, but they are now getting taller and taller, over 60 storeys. The ones in the photo with the streetcar above line the foot of Spadina Avenue. There are proposals for a cluster of three Frank Gehry designed towers of over 80 storeys on King Street West in the entertainments district – see the photo below.

One consequence of all the residential construction in the central city is that many streets have taken on a vitality that they may not have had previously; there is a wide diversity of clubs and cafes, and also supermarkets. Another consequence is that many employees in the central city now bike or walk to and from work. The photo on the right shows the bike rack outside the Commerce Court – the Bank of Commerce skyscraper. However the towers radically change the shape of the streets in a way that mid-rise buildings do not, and even though they may have street front shops at ground level this is not, I think, a change for the better. As condominiums they will need to be maintained by monthly maintenance fees paid by their owners; in the short term this may not be an issue, but in 25 or 30 years when elevators and cladding may have to be replaced or repaired the scale and expense of repairs could pose a problem. In short, I think these glassy, skyscraper condominiums are ill-advised.

One consequence of all the residential construction in the central city is that many streets have taken on a vitality that they may not have had previously; there is a wide diversity of clubs and cafes, and also supermarkets. Another consequence is that many employees in the central city now bike or walk to and from work. The photo on the right shows the bike rack outside the Commerce Court – the Bank of Commerce skyscraper. However the towers radically change the shape of the streets in a way that mid-rise buildings do not, and even though they may have street front shops at ground level this is not, I think, a change for the better. As condominiums they will need to be maintained by monthly maintenance fees paid by their owners; in the short term this may not be an issue, but in 25 or 30 years when elevators and cladding may have to be replaced or repaired the scale and expense of repairs could pose a problem. In short, I think these glassy, skyscraper condominiums are ill-advised.

[NOTE: In my book I reference a 2007 report by the City of Toronto titled Living Downtown, which indicated that the population of the central area had increased by 70,000 since the 1970s. I have just come across a more recent version of this, “Living Downtown and in the Centres” 2012 which updates that. I have become increasingly convinced that the current level of high-rise condominium construction downtown is ill-advised, in part because it is fundamentally changing the character of the streets around the downtown core, but also because managing these skyscraper apartment buildings as condominiums will become increasingly difficult as difficult and costly maintenance issues arise.

In February 2014 I added a long post to this website “Condominium Apartment Skyscrapers in Downtown Toronto” that examines my concerns, especially about the residential towers of more than 70 and 80 storeys that are now being proposed.]

A Skyscraper City

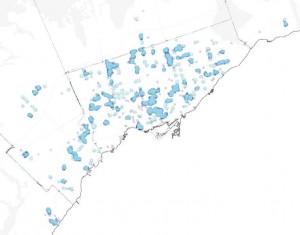

The high-rise condominium boom is concentrated around the downtown core, but also spreads across the city. It has reinforced the already considerable number of high-rise residential buildings that had been built in the Metro era. The result is that Toronto is variously ranked as either the second city in the world after New York for high-rises of 12 stories/35 metres or more (a total of 1978 buildings in Dec 2013, Skyscraperpage.com), or seventh (after Hong Kong, New York, Tokyo, Chicago, Dubai and Shanghai) for skyscrapers of 100 metres or more (187 buildings, Emporis.com). Most of the latter are in and around downtown; the former are scattered across the City of Toronto and to a lesser, though not inconsiderable, extent into the outer suburbs.

This map from a 2010 report on tower renewal in the Toronto Region by the Centre for Urban Growth shows clusters of high-rise apartments. Dark blue circles are clusters of 5 or more, pale blue are 2 to 4, dots are isolated towers. The condominium boom continues to add to these. Skyscraperpage lists (in September 2013) 38 skyscrapers of 50 stories or more proposed or under construction in Toronto. There was a interesting report with good graphics on Vertical Toronto in the Toronto Star in 2011.

Toronto as a skyscraper city in 2012. The downtown office towers and CN Tower on the right, to the left of those are condominiums, and then scattered across the rest of the city are Metro era apartments and recent condominiums. Some of the proposed skyscraper condominiums will have over 80 storeys (for instance three towers on King Street West designed by Frank Gehry) and will begin to rival the tallest office buildings.

Reurbanization

For all its street-front retailing the old City was a dreary place in 1970, and the commercial strips in the rest of Metro were uninspiring (see photos in the entries for Chapter 1 and Chapter 4). In the last four decades that has changed dramatically. Along streetcar routes main streets are now lined with patio restaurants, small shops and galleries, while many residential neighbourhoods have been extensively renewed or gentrified. The distinctive cultural or historical identities of commercial areas have been recognized, and the pedestrian environment improved, in Business Improvement Areas – an idea invented in Toronto in 1970 and now used internationally (but usually called business improvement districts.) There are now 75 of them in Toronto.

The photo on the left is of Bloor West Village in 1971, the first Business Improvement Area in the world according to Wikipedia, with then recently planted street trees and planters installed using funds from a voluntary tax on local businesses to pay for such improvements. The photo on the right shows Queen Street West, one of many flourishing main streets near downtown, in 2012. In the broad sense of the word, these sorts of improvements constitute reurbanization – making the city more vital and more attractive for pedestrians, and giving shopping streets a chance to compete with malls and plazas, such as the Eaton Centre. Toronto is certainly not unique in its awakening of street life in the last forty years – it has also happened in other cities I am familiar with, including London, Washington D.C., Seattle, Portland and Vancouver. What is perhaps distinctive about Toronto is the sheer scale of it, as suggested in Duany’s statement that there is more street-oriented retailing here than in all the sun-belt cities combined. And this revitalization is not only a matter of restaurants and small shops; it also involves sports arenas, and major institutions who bring in internationally famous architects to replace or add to their facilities. Here are a couple of examples from central Toronto.

The photo on the left, with a colourful CN Tower at dusk, shows part of the giant shoebox on stilts raised above older buildings for the Ontario College of Art and Design, by the British architect Will Alsop. The photo on the right is of the crystal addition to the Royal Ontario Museum by German architect Daniel Libeskind (with conventional commercial towers along Bloor Street in the background).

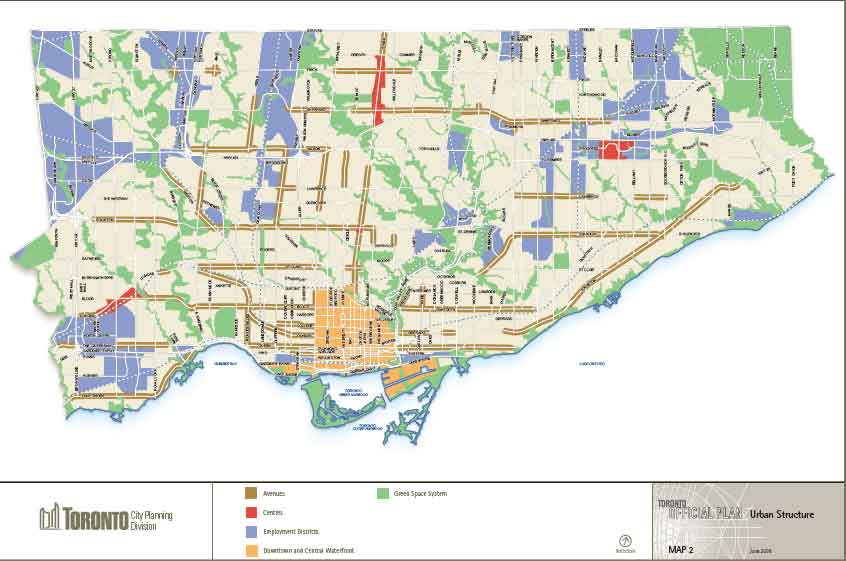

The Official Plan for the City of Toronto (which since 1998 means the former Metro – explained in my book), identifies old main streets and suburban arterials as ‘avenues’ and proposes that they be used for intensification as one way to maintain growth in the post-suburban city. Some indication of how successful this has been in indicated in some of the recent bulletins and background reports prepared (mostly in 2012), for the review of the Official Plan, such as the Bulletin “How Does the City Grow” available here.

Intensification takes various forms, depending on the character of a particular avenue. The photo on the left below shows a new condominium building on Avenue Road in North Toronto. The illustration on the right shows a proposal from a 1991 report on reurbanization by consultants Berridge, Lewinberg, Greenberg for intensifying suburban commercial strips by filling in street front parking lots with apartments and commercial uses, and putting in a light rail line.

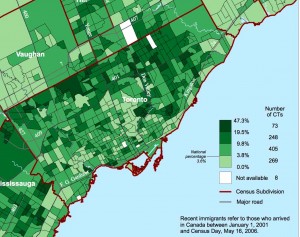

To some degree the process of intensification in the inner suburbs has been overtaken, or at least supplemented by immigration, which in the four decades or so since 1970 has contributed enormously to urban revitalization because immigrants have taken over many small business in commercial strips and given them a new identity.  This map from Statistics Canada, 2006 Census, shows the percentage of recent immigrants in the City, those who had arrived in the previous 5 years. The darkest colours are the highest percentages, and what the map indicates clearly is that immigration is concentrated in the inner suburbs. The lightest area in the centre is adjacent to Yonge Street. Below are a couple of examples showing the impacts of immigration on streetscapes – the Dragon Mall in Scarborough about 1990, and the mixed Korean and Persian commercial strip along Yonge Street in North York in 2009 (with Pizza Pizza, a Toronto chain that began in the 1960s). As with urban revitalization in general, Toronto is not unique in its increasing cultural diversity. It is, however, exceptional for the scale of it – about half the population is foreign born, and almost half are visible minorities.

This map from Statistics Canada, 2006 Census, shows the percentage of recent immigrants in the City, those who had arrived in the previous 5 years. The darkest colours are the highest percentages, and what the map indicates clearly is that immigration is concentrated in the inner suburbs. The lightest area in the centre is adjacent to Yonge Street. Below are a couple of examples showing the impacts of immigration on streetscapes – the Dragon Mall in Scarborough about 1990, and the mixed Korean and Persian commercial strip along Yonge Street in North York in 2009 (with Pizza Pizza, a Toronto chain that began in the 1960s). As with urban revitalization in general, Toronto is not unique in its increasing cultural diversity. It is, however, exceptional for the scale of it – about half the population is foreign born, and almost half are visible minorities.

Suburban Downtowns

The deconcentration policy of the 1970s (there’s a map above) identified several centres for intensification including two “Major Metropolitan Centres” – North York and Scarborough. The Official Plan for the City now identifies these (and Etobicoke at the western end of the Bloor Subway line, and Yonge-Eglinton) simply as “centres” (red splotches on the OP shown above). North York and Scarborough were separate municipalities within Metro until the amalgamation in 1998, each then with populations of over 600,000 and their own city halls. Their plans for creating distinctive, albeit suburban, downtowns had begun even before the deconcentration policy and were in advanced stages of implementation.

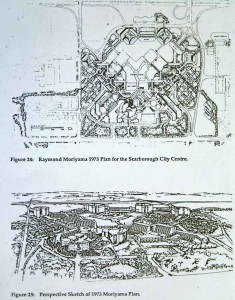

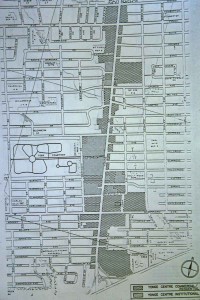

The drawing on the left above shows the 1973 plan by Raymond Moriyama (a well-known local architect and designer of Scarborough Civic Centre) for Scarborough City Centre. The Y-shaped structure is a shopping mall that had then just been opened. The map on the right is a conceptual land use plan for North York downtown from about 1980, and shows its the linear form along Yonge Street.

The photo on the left shows the skyscrapers of downtown North York, looking north along Yonge Street from the city border with Toronto in 1997, just before amalgamation. The sign describes it as the sixth largest city in Canada. The photo on the right is of Canada Day celebrations at Scarborough Civic Centre in 1978. Amalgamation stripped away their political identity, but these suburban downtowns have both continued to expand and intensify. North York has a vibrant street life along Yonge, though Scarborough, with an enclosed shopping mall at its centre, is still a bit bleak in spite of recent condominium construction and some attempts at pedestrianization. The former city halls are now used as branch offices in the amalgamated City of Toronto.

Yonge Street in downtown North York is lined with office towers and condominiums. The small stores on the other side of the street are remnants of the main street commercial strip that developed in the 1920s when the radial street car ran here. The photo on the right shows part of Scarborough downtown – the weird installations line the entrance road to the shopping mall, the towers are condominium apartments, the peaked white roof is a federal government office building.

City versus Suburb

The imposed amalgamation of the municipalities within Metro in 1998 has not resolved the division that became clearly manifest in the Stop Spadina protest between the old City, the part built-up before 1940 around streetcar lines and railways, and the auto-oriented inner suburbs, mostly built in the 1950s and 1960s. The inner suburbs wanted the expressway, the old city didn’t. Politically, and to some extent socially, the two parts of the new City of Toronto have different attitudes. Below are two images that capture some of that difference. The mural of the streetcar in just off Queen Street West, a part of the old city where streetcars are celebrated, life revolves around revitalized main streets along their routes, and cars are at best considered unfortunate necessities. On the right is Yorkdale Mall, which opened in 1964 at the intersection of Highway 401 and what would have been the Spadina Expressway. It has recently been upgraded and expanded and is filled with upscale fashion stores (including one for Tesla cars). It does have a subway station but its parking lot is rarely less crowded than this. I have no doubt that people who live in the old city shop at Yorkdale, and those who live in the inner suburbs visit or work in the central city, but there is no question that the two are uneasy bedfellows.

Finally, a quote from Dennis Lee’s poem Civil Elegies, published by Anansi in 1972, that captures well the downtown resistance to planning and celebrates the organized complexity that was championed by Jane Jacobs and others.

…The crowds emerge at five from jobs/ that rankle and lag. Heavy developers/ pay off aldermen still; the craft of neigbhourhood, its whichway streets and generations/ anger the planners; they go on jamming their maps/ with asphalt panaceas.